I rarely write about my personal history, but when I was in Red Cloud, Nebraska, Willa Cather’s hometown, I found myself remembering some Cather-style details from my childhood. Most of this post was written then.

The emails and comments in response to my road trip post have been gratifying. But I want to correct a common misconception, which is that this trip somehow represents my first venture into “flyover land.” The obvious objection is that from 2000 to 2007 I lived in Dallas, which isn’t even near the coast. But there’s a bigger mistake behind the assumption. There are indeed people in my line of work who have lived their entire lives in elite enclaves within coastal metropolitan culture. (As one used to remark, “It took three generations for my family to get from Brooklyn to Manhattan.”) I am not one of these people.

I am a provincial, a native of the rolling hills of the Carolina Piedmont. I grew up talking like an old-time country music singer, only with better grammar and less colorful turns of phrase. My upbringing was utterly parochial. That doesn’t mean I was anything as marketable as a hillbilly from a dysfunctional blue-collar family. I came from mostly teetotaling, usually college-educated, overwhelmingly Presbyterian stock—the dutiful pillars of the community that both cosmopolitan and good ol’ boys find risibly, if not obnoxiously, staid.

I was born in Asheville, North Carolina, moved to Columbus, Georgia, when my father was called up out of the Army Reserve during the Berlin Crisis and stationed at Ft. Benning1, then to Rome, Georgia, when he was discharged. We moved to Greenville, South Carolina, in 1964, when I was 4, and I lived there until I went to college. Many places claim to be the Buckle of the Bible Belt, but the home of Bob Jones University makes the best case. As my father used to day, “This is a place where a lot of people think Billy Graham is a dangerous liberal” or words to that effect. I grew up in a cultural bubble. Although my parents were better educated and more liberal than most of the town, our lives revolved every bit as much—more, in fact—around church.

My father’s father was a Presbyterian minister. Unusual for the South, he and my grandmother were city people, natives of Atlanta, and had lived in Houston, Richmond, and Charlotte for most of their marriage. But when I was a child, they were ensconced in Toccoa, Georgia (population ~7,000). My grandfather was the chief administrator of Athens Presbytery, which meant he had a home office and a secretary (and a dictaphone using wax cylinders, which I loved). I’m not sure what his administrative duties were, but a big part of his job was serving as a 20th-century circuit rider, driving his Rambler to tiny country churches to preach. I often went with him, visiting places like Mt. Airy and Cornelia, where congregations numbered in the 10s and people sang “Rock of Ages” in a nasal twang.2 Presbyterians are scarce in north Georgia.3

Those little country churches were quite a change from my family’s church, with its magnificent sanctuary built in a mid-century modern take on gothic architecture. There the music featured a grand pipe organ, paid soloists, and a music director whose tastes ran to Bach and Vaughn Williams. The theology was as sophisticated and as unapologetic as the music. It was, and is, a theologically liberal church—a very large one today, contrary to broader trends among mainstream Protestant congregations—but one in which people talk easily about God and espouse core Christian beliefs. My upbringing left me with the conviction that you do actually have to believe to call yourself a Christian. I converted to Judaism in my 20s, though not to get married as people often assume.

Every summer we drove to Little Rock to visit my mother’s family. In the early years, this was a southern trip, through Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, then up to Memphis to cross the Mississippi. When I-40 was completed, we went north and I learned just how long Tennessee is and how distinctive its three big cities are. I saw plenty of pretty scenery and also some deep rural poverty on those drives. The poverty was especially prominent between Memphis and Little Rock.

I went to Branson, Missouri, before it was famous. As children, we used to be excited when Silver Dollar City turned up on reruns of The Beverly Hillbillies.

I hated shoes. I took them off as soon as I got in the house, once kicking one off through a window. My grandfather used to joke, lamely, that we should have a contest between me and a magician to see who could make shoes disappear faster. I went barefoot anywhere and everywhere I could, which was pretty much any place but school and church—including the grocery store (where the soles of my feet soon became black) and the wild plum and blackberry patches on the vacant lot a few houses down. My mother warned me to wear shoes in the latter: “Snakes love blackberries.” Fortunately, I never saw a snake.

We kids loved “the plum patch,” which also had a tree suitable for climbing. The wild plum trees were on one side of the remnants of an old road, the blackberry bushes on the other side. Once I picked some of the nicest plums, polished them up, and went around the neighborhood knocking on doors and offering them at a penny each. I can only imagine how amused the adults must have been. Another time, my mother made wild plum jelly. It was a beautiful pinkish orange but horribly bitter, like the skins of the fruits, which you had to spit out. She had a friend who was working in some sort of anti-poverty program. They decided to pull a prank on her boss. Adopting the persona of a sympathetic old lady, my mother wrote a note praising the wonderful work they were doing for the disadvantaged and sending a jar of jelly in appreciation

We always knew that the plum patch belonged to someone and would eventually be bulldozed to make way for a house, as it eventually was.

I attended public schools that can be charitably called mediocre. My middle school and high school were socioeconomically diverse in an almost mythical way.4 They had students who lived in public housing, students who lived on 10 acres, and everything in between. About 25 percent of the student body was black, the rest white, except for two Asians. That Judy and David Bernstein were among the rare Catholics captures the religious diversity.

Up through sixth grade, the school day began with explicitly Christian devotionals. Reading the local paper, I used to be confused by the many letters to the editor railing against the Supreme Court for banning prayer from public schools. How could that be if Little Visits with God was practically part of the official curriculum? People who think that the culture wars began with Roe v. Wade get it wrong. “Taking God out of the schools” was what set people off, at least in the South. Protestant Christianity was as pervasive and uncontroversial as iced tea. The idea that anyone might feel ostracized by routine Christian lessons and prayers was hard to grasp. It struck people as an attack.

We had some good teachers and a few excellent ones. But the schools were cheaply provisioned and lacked air conditioning, among other resources. It isn’t news to me that extreme heat can dull your brain. I remember an excruciatingly hot, humid day in fourth grade when I struggled with what should have been a simple exercise: multiplying three digit numerals—say, 387 x 496—then reversing their order, 496 x 387, and getting the same answer. Over and over I kept making errors and having to repeat the process. Finishing the ten or so problems seemed to take an eon.

I also remember how my fantastic seventh-grade social studies teacher—a Boston native and Yale graduate who spent a few eye-opening years teaching down South—used to have enormous pools of sweat all the way down each side of his shirts. If the students were miserable, the teachers had it worse. I can only imagine how uncomfortable my female high school teachers must have been in their polyester pants suits.

Our curriculum was limited for lack of funds. Algebra wasn’t offered before ninth grade, so getting to calculus required doubling up on math classes in our sophomore and junior years. I opted against the double load as a junior, only making it to pre-calculus. (I took calculus as a college sophomore.)

Every high school course required at least 15 students, which meant third-year foreign languages were scarce. To offer AP Biology, the teacher rounded up both juniors like me and seniors, including that year’s valedictorian who’d already aced the class the year before. With roughly 1,000 students in four grades, the school wasn’t especially small. But it was academically diverse and academic ambition was rare, even among those with high test scores. Those of us who took advanced classes were generally interested in them. We were seeking knowledge more than credentials.

When the high school guidance counselor asked me what books I liked, I said The Sound and the Fury. His befuddled response suggested he thought it was a bodice-ripper along the lines of Kathleen Woodiwiss’s huge bestseller The Flame and the Flower. I sold a lot of her books when I worked in a local bookstore, along with many copies of The Joy of Sex and, for the pious, The Total Woman. Sometimes black customers from a nearby poor neighborhood would put Roots, then in hardback, on layaway until they paid off the $13 price ($12.50 plus tax). The only products exempt from South Carolina’s 4 percent sales tax were Christian bibles and commentaries. We had to remember that when we rang them up.

The high school librarians kept James Joyce’s Ulysses behind the front desk to protect against local busybodies who would sometimes go looking for offensive literature to make a fuss about. Their discretion wasn’t a problem. Not even I wanted to read Ulysses.

Stunned by my high SAT scores and advised by my mother’s cosmopolitan best friend, I became the first person in my high school’s 13-year history to apply to an Ivy League college. (A guy a few years ahead of me went to Stanford.) There was a legendarily good science student before my time who had gone to MIT but come back after an unpleasant year. Nearby Furman vacuumed up most of the school’s talent.

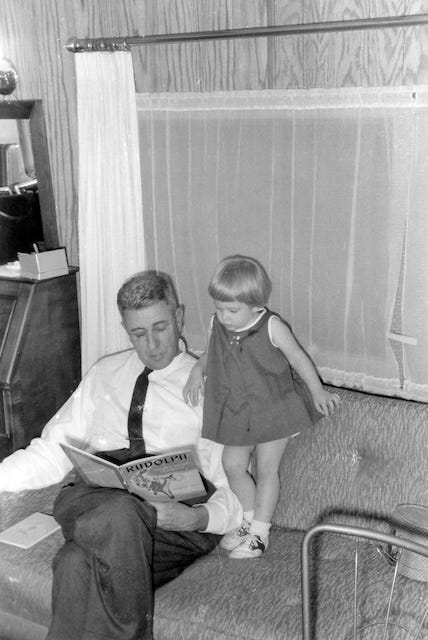

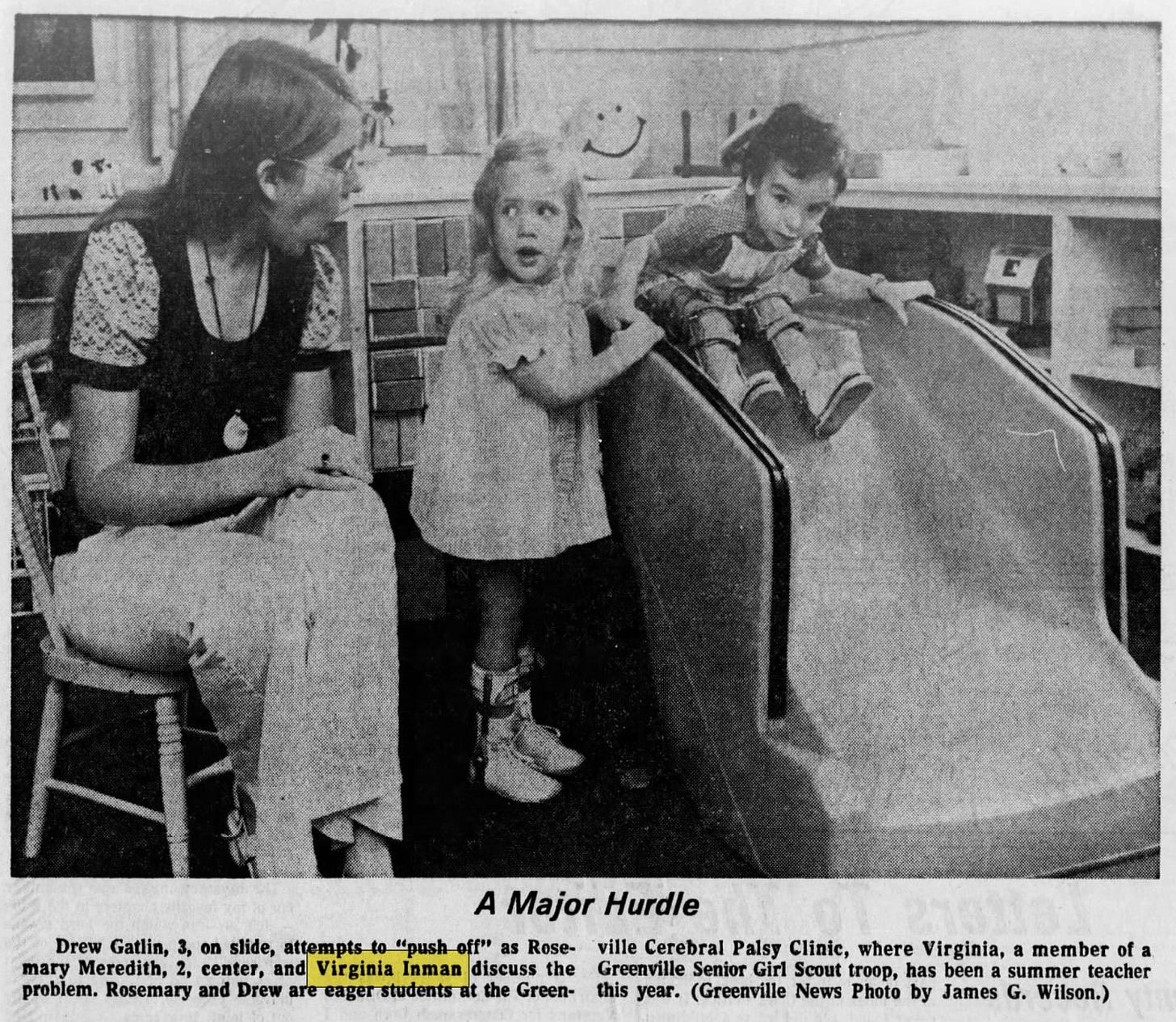

In our small city, I learned from personal experience not to trust everything in the newspaper. As part of a United Way package, The Greenville News ran this photo of 13-year-old me and managed to make two errors in the caption.

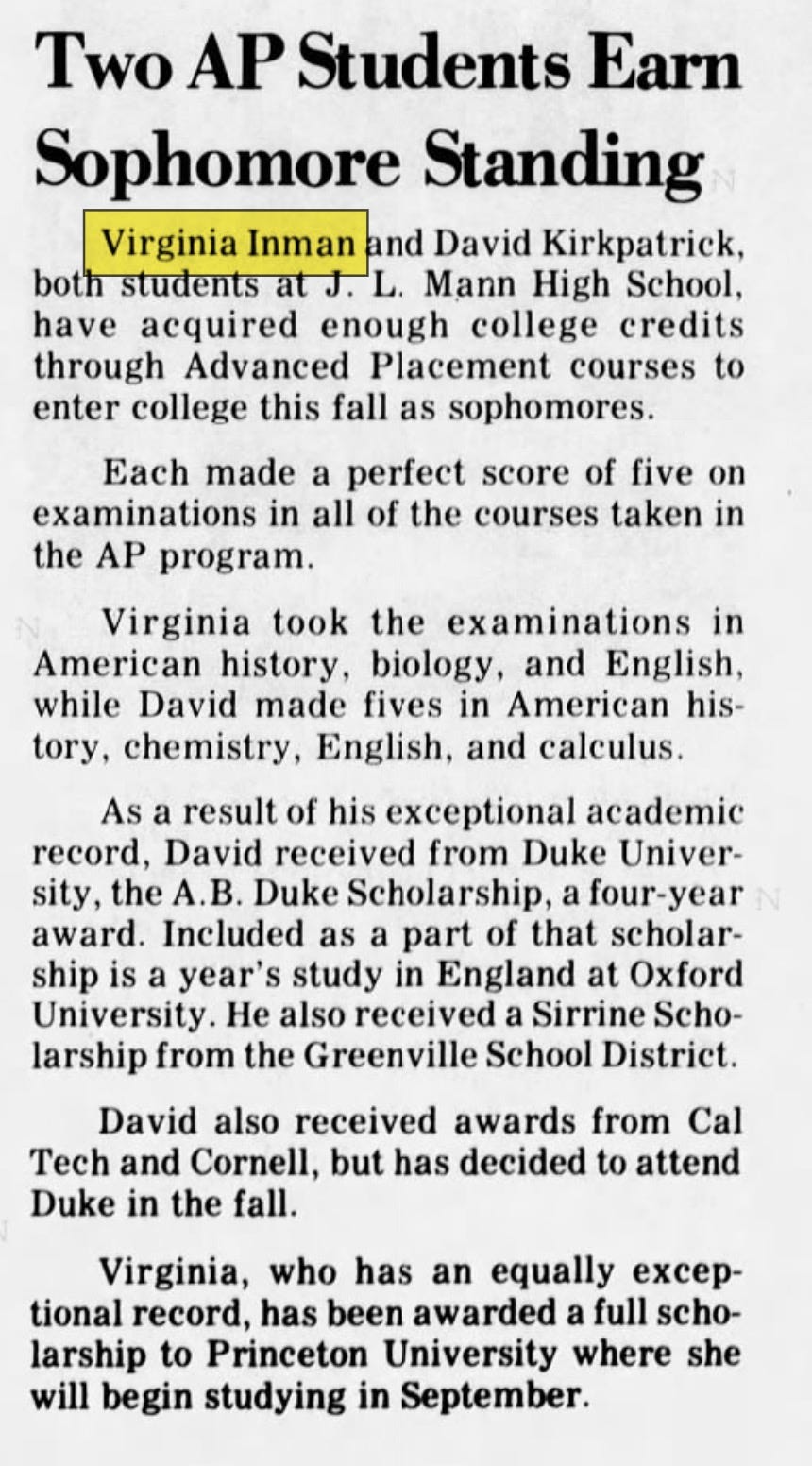

But at least those mistakes were mere sloppiness. This story, from my senior year in high school, was more egregious.

Neither of us entered college as a sophomore, but the part about David is mostly accurate. Our valedictorian, he did go to Duke on an A.B. Duke scholarship.

But I did not get a cent from Princeton. Someone at either the paper or the school district simply made that up. It wasn’t a distortion but an outright fabrication. No one bothered to check with me, much less with Princeton. In a town as provincial as Greenville in 1978, people would believe just about anything about famous schools far away. They had no concept that Ivy League schools didn’t offer academic scholarships or that a star student in Greenville wouldn’t be especially impressive in Princeton’s student body.

Nowadays, someone in my economic position—my father was an engineer, my mother a poorly paid adjunct English instructor—would in fact get a full ride at Princeton. But someone with my background probably wouldn’t get in. Although the population of South Carolina has grown rapidly since my time—it’s now the 23rd largest state rather than the 40th—and the Princeton student body has expanded by more than 1,000 students, the number of South Carolinians admitted to Princeton has actually dropped. With 13 in my freshman class, it didn’t have much room to fall.

During this stint, we lived in what I called “my trailer house,” known more classily as a mobile home.

Not to be confused with the Jewish version, popular at Hannukah.

My grandfather told me a story about a scholarship fund that had been endowed to benefit a black Presbyterian orphan, defined strictly as having no living parent. Even nationally, black Presbyterians are scarce. In north Georgia in the 1960s, they were nonexistent. He used to joke they should find a qualified orphan willing to convert.

Up until about October of my fourth grade year, our schools were de facto segregated thanks to a “freedom of choice” system where the only way a black student would end up in a white school was to have very determined parents. Before court-ordered full integration, there was one black girl in my class, the daughter of a pediatrician.

Virginia, I’m a few years older than you and grew up a few miles to the west in the mountains of WNC in the 1940’s and ‘50’s. Graduated high school in Asheville in 1960. We were the only Jewish family in small paper mill town of canton west of Asheville. Your story rings a lot of bells. I’ve written a memoir about what being a Jewish hillbilly was like.

Really well written. I’d love to read more about how your time at Princeton went. To me, Princeton is a mythical place, like Hogwarts, and I can imagine it was a wildly different place from where you grew up