The Technocratic Temptation

Just sweep everything away and build from scratch....What could possibly go wrong?

This afternoon I went to Hilbert Museum of California Art, which is owned by Chapman University. By sheer coincidence, it was the penultimate day of an exhibition of works by Millard Owen Sheets (1907-1989), who is best known for the many mosaic murals he made for buildings in southern California. One I used to pass in Santa Monica is now on the front of the museum. But Sheets worked in many different media, as the exhibit highlights.

Many of his works sympathetically portray poor people, not as victims but as human beings going about their lives. Above on the right is a painting of L.A.’s Chavez Ravine, where many Mexican-American families lived and owned houses. On the left is a print that served as a study for this oil painting, now in the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum, where it bears the more pejorative name “Tenement Flats.” It depicts the area of downtown L.A. known as Bunker Hill, where by the 1930s old mansions had become crowded housing for poor families.

Neither neighborhood exists today and they didn’t disappear because real estate developers came in and flipped properties bought at market prices. Both were involuntarily wiped out in mid-20th-century slum clearance programs backed by eminent domain. Bunker Hill made way for municipal office buildings and arts venues. Chavez Ravine became the site of Dodger Stadium. (Click on the links for photos and more detail on these complicated histories.)

As sympathetic as I am to the sentiment that “it’s time to build,” I worry that many of today’s would-be builders have either forgotten or never understood the mistakes of their 20th-century predecessors. Just because you’re smart and think something is a good idea doesn’t mean it is. The great thing about market prices is that they convey information about how much people actually value things. If Walter O’Malley had had to pay Chavez Ravine property owners high enough prices to get them to voluntarily sell, the Dodgers might still be in Brooklyn.1

This is the heart of my husband Steven Postrel’s comment, in response to my previous post, in which he denounces Steven Teles and Rob Saldin’s Hypertext essay on “the abundance faction.”

That one paragraph you quoted from Teles and Saldin's Hypertext essay is by far the most congenial to dynamism. The rest of the parts that aren't about political strategizing read like a technocratic screed, one innocent of the last 100 years of thinking about incentives and information and the hazards of government planning. It sounds like Robert Moses envy, or Chinese Communist Party envy, or Woodrow Wilson envy, or FDR envy….That they constantly talk of coalitions with “business” but never use the term “markets” is a warning sign about their vision, which seems to be less about permissionless innovation and private property and contract rights to build things than it is about empowering dirigiste bureaucrats to run transmission lines through your backyard in the name of amorphous climate change concerns.

I think he’s giving the essay an unduly uncharitable reading, but the point he makes is one many in the abundance coalition too often ignore. Right now, I’m happy to ally with people who want to jettison the precautionary mindset that demands ever-increasing regulation and continually multiplies veto players. But eventually we’ll have to fight about just how much leeway the would-be builders get.

Many of our current problems stem from the backlash against the sweeping redevelopment efforts done by government at all levels in the mid-20th century. We replaced the top-down redesign of cities with procedures that made voluntary building more difficult. Simply going back to the “good old days” doesn’t solve the underlying problems of knowledge and permission. For that, you need to leave most building to markets and demand a high burden of proof—and true market pricing for eminent domain purchases—from government projects.

When today’s critics equate techno-optimism with techno-fascism, this is what they’re afraid of: Progress means smart people sweeping away whatever you value and deciding how everyone will live. Don’t be like that!

Two related essays from two recommended Substacks

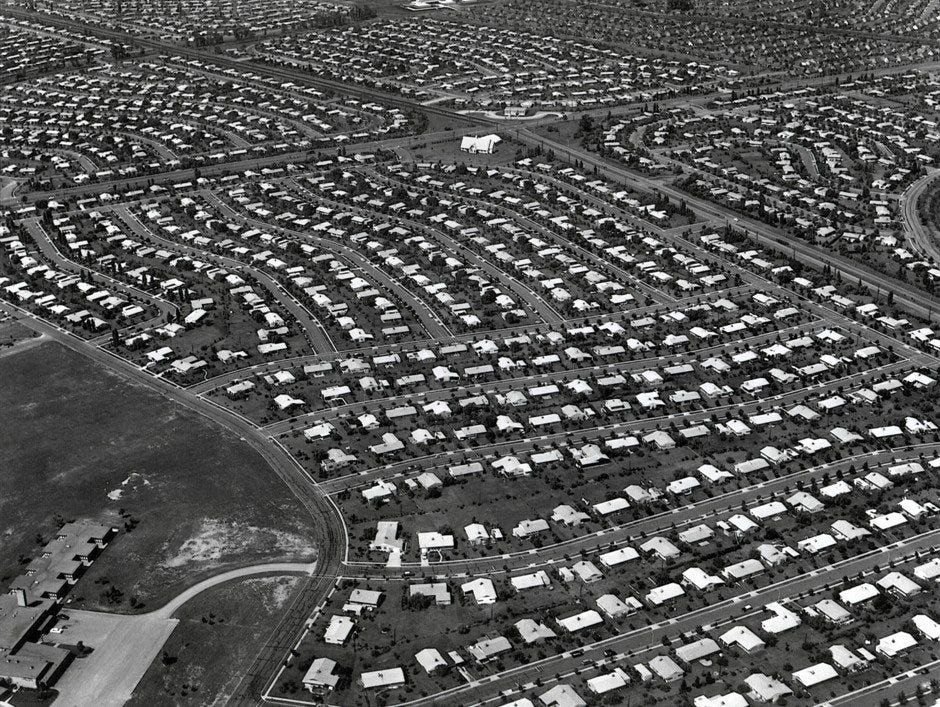

at has a must-read essay on why Levittown didn’t revolutionize housing construction. It explains both how the company made mass construction of single-family homes super efficient and why its techniques stopped working. Here’s a key selection: Another factor which created headwinds for Levitt’s large-scale building strategy, particularly from the second half of the 1960s onward, was the growth in land use controls and restrictions. Immediately following the war, land development and housing construction had been relatively straightforward. Local opposition to new construction was minor and not particularly effective, and local jurisdictions, not wanting to be seen as getting in the way of building homes for veterans, were more than willing to work with developers. On the first Levittown, for instance, Levitt was able to get the local building code amended to allow homes without basements.

But by the end of the 1960s, opposition to new development became much stronger, partially because of anti-growth tendencies within the rising environmental movement. Land use controls became much stricter and more burdensome. Jurisdictions which previously had worked with homebuilders to try and encourage growth were now at best indifferent, and at worst hostile to it. In his history of merchant homebuilding, Ned Eichler notes that “places like Fairfax County (Virginia), Montgomery County (Maryland), Ramapo (New York), Dade County (Florida), and Boulder (Colorado) not only adopted growth limiting programs but imposed absolute moratoria." Levitt’s fourth Levittown was stopped in its tracks in 1971 when Loudoun County, Virginia refused the rezoning required, even after Levitt offered to pay for all the new facilities (such as schools) the development would require. The city of Boca Raton in Florida made headlines that same year when it passed a law limiting the amount of housing that could ever be built there to 40,000 units. California became especially restrictive in allowing new home building: by 1975, according to Eichler, “most California cities and counties had growth control policies and procedures of varying restrictiveness.” But while California was an early vanguard of anti-growth policies, the trend was national. A 1973 survey found that 19% of local governments across the U.S. had initiated some type of temporary development moratorium.

Not only did land use controls and development restrictions slow down and prevent new home construction, but they drove up the price of land, and thus the cost of all other homes. A 1968 report from the National Commission on Urban Problems noted that “the net effect of public land use policy is to reduce the supply of land available for modest cost housing and thus to increase its cost.” As late as 1969, these restrictions were still comparatively minor nationally: in a 1969 survey from the National Association of Home Builders, just 3% of homebuilders mentioned building codes or zoning as their most significant problem. But by 1976, that had risen to 38%, by far the most severe problem listed by builders. Between 1969 and 1975, average land cost per square foot for new housing rose 15% per year.

By the 1970s, when building was allowed at all, homebuilders found themselves subject to an “arduous, long, and expensive process” of approvals, as well as being forced to meet higher (and more expensive) standards for things like sidewalks, and pay for things such as street extensions, for which the government had previously footed the bill.

My husband’s first home was in the Pennsylvania Levittown, pictured below.

In this post,

of makes the strongest dynamist case for Trump, although he frames it differently. Exhibit A is Operation Warp Speed:While Trump can’t take sole credit for the program, it is hard to imagine such a large and relatively unfettered public-private-partnership emerging through the stakeholder-based politics of modern “everything bagel” liberalism. In fact, the special authorizations employed by OWS were downstream of an existing deregulatory push at FDA, spearheaded by the same Philipson quoted above and his Chicago School colleague, Casey Mulligan….

OWS wasn’t the only EA-aligned health policy adopted by the last Trump administration. Trump also took on the kidney shortage by establishing reimbursements for the expenses incurred by living donors alongside expanded support for home-based dialysis and various other fixes. Given kidney disease accounts for 7% of Medicare’s entire budget, these reforms plausibly saved billions of dollars and tens of thousands of Quality Adjusted Life Years. And yet the reforms were only possible thanks to Waitlist Zero, an EA-affiliated advocacy org, and the cohort of Federalist Society lawyers running policy at HHS. It would be surprising if a second Trump term didn’t provide similar opportunities for libertarians and EAs to team up once again.

I highly recommend the essay, although it doesn’t persuade me to vote for Trump.2 Trump is too erratic and too contemptuous not only of technocratic norms but of liberal ones. (It’s worth noting how often his enemies conflate the two.) And while Sam and I both embrace Operation Warp Speed, Trump’s anti-vaccine base doesn’t, which means he’s distanced himself from his administration’s most impressive achievement. Count me as still #NeverTrump. But arguments like Sam’s—and Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz’s—make me slightly less pessimistic about a second Trump term. Slightly.

Subscribe to my YouTube channel

Please!

I’m going to keep bugging you until I get to 10K subscribers!

O’Malley bought the land from the city of L.A. for less than the city had paid the federal government for it. The federal government originally acquired it for public housing, which subsequent city administrations opposed. It’s a complicated story.

A question that is purely theoretical for Sam, a Canadian. I don’t have an alternative country if this one goes down the tubes.

Donald Trump has promised to deport 15-20 million people and right now the GOP has PEPFAR in its crosshairs. Sam’s piece isn’t an argument, it’s completely divorced from reality.

I agree! This is one reason I'm always a bit suspicious of social housing. I don't know if allocating largesse to communities with the most political power is any better than doing it through the market.