The Lost Glamour of the Future

Can we bring it back? Do we want to? Plus a futuristic offer from the past and some news about my next book, which isn't what you might expect.

The new issue of Works in Progress includes my magnum opus on why “the future” was glamorous for the first two-thirds of the 20th century, why it lost its glamour, and what restoring that glamour would entail. It weaves together ideas and examples from The Future and Its Enemies and The Power of Glamour with new material. I believe it has important things to say to the burgeoning progress and abundance movement. I hope everyone will read it. Here’s the opening:

Progress used to be glamorous. For the first two thirds of the twentieth-century, the terms modern, future, and world of tomorrow shimmered with promise.

Glamour is more than a synonym for fashion or celebrity, although these things can certainly be glamorous. So can a holiday resort, a city, or a career. The military can be glamorous, as can technology, science, or the religious life. It all depends on the audience. Glamour is a form of communication that, like humor, we recognize by its characteristic effect. Something is glamorous when it inspires a sense of projection and longing: if only . . .

Whatever its incarnation, glamour offers a promise of escape and transformation. It focuses deep, often unarticulated longings on an image or idea that makes them feel attainable. Both the longings – for wealth, happiness, security, comfort, recognition, adventure, love, tranquility, freedom, or respect – and the objects that represent them vary from person to person, culture to culture, era to era. In the twentieth-century, ‘the future’ was a glamorous concept.

Joan Kron, a journalist and filmmaker born in 1928, recalls sitting on the floor as a little girl, cutting out pictures of ever more streamlined cars from newspaper ads. ‘I was fascinated with car design, these modern cars’, she says. ‘Industrial design was very much on our minds. It wasn’t just to look at. It was bringing us the future.’

Young Joan lived a short train ride from the famous 1939 New York World’s Fair, whose theme was The World of Tomorrow. She went again and again, never missing the Futurama exhibit. There, visitors zoomed across the imagined landscape of America in 1960, with smoothly flowing divided highways, skyscraper cities, high-tech farms, and charming suburbs. ‘This 1960 drama of highway and transportation progress’, the announcer proclaimed, ‘is but a symbol of future progress in every activity made possible by constant striving toward new and better horizons.’

‘All I wanted to do,’ Kron says, ‘was go into the World of Tomorrow.’ She wasn’t alone. Anticipating a bright future was a defining characteristic of the era, especially in the United States.

When Disneyland opened in 1955, Tomorrowland embodied the promise of progress. A plaque at the entrance announced ‘a vista into a world of wondrous ideas, signifying man’s achievements . . . a step into the future, with predictions of constructive things to come.’

Back then, the Year 2000 and the Twenty-first-century were glamorous destinations. Newspaper features and TV documentaries described a future filled with barely imaginable wonders. A 1966 New York Times article titled ‘A Glimpse of the 21st Century’ predicted ‘a world virtually free of deserts, smog and engine noise, comfortably supporting a population ten times that of today – from 25 to 50 billion’, thanks to abundant nuclear power. There would be resorts on the bottom of the ocean and underground conveyor belts transporting bulk cargo. Underground electric trains would whisk passengers from city to city while electric air buses carried them across town. These were not idle speculations, the Times assured readers, but serious scientists’ efforts ‘to extend present trends a few decades into the future’.

As a child, I felt lucky to be born in 1960. I’d be only 40 in the year 2000 and might live half my life in the magical new century. By the time I was a teenager, however, the spell had broken. The once-enticing future morphed into a place of pollution, overcrowding, and ugliness. Limits replaced expansiveness. Glamour became horror. Progress seemed like a lie.

Much has been written about how and why culture and policy repudiated the visions of material progress that animated the first half of the twentieth-century, including a special issue of this magazine inspired by J Storrs Hall’s book Where Is My Flying Car? The subtitle of James Pethokoukis’s recent book The Conservative Futurist is ‘How to create the sci-fi world we were promised’. Like Peter Thiel’s famous complaint that ‘we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters’, the phrase captures a sense of betrayal. Today’s techno-optimism is infused with nostalgia for the retro future.

But the most common explanations for the anti-Promethean backlash fall short. It’s true but incomplete to blame the environmental consciousness that spread in the late sixties. Rising living standards undoubtedly led people to value a pristine environment more highly. But environmental concerns didn’t have to take an anti-Promethean turn. They might have led instead to the expansion of nuclear power or the building of solar energy satellites. Cleaning up smoggy skies and polluted rivers could have been a techno-optimist enterprise. It certainly didn’t require curtailing space exploration. Eco-pessimism itself needs a fuller explanation.

Read the rest here.

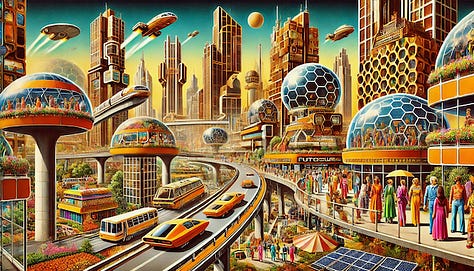

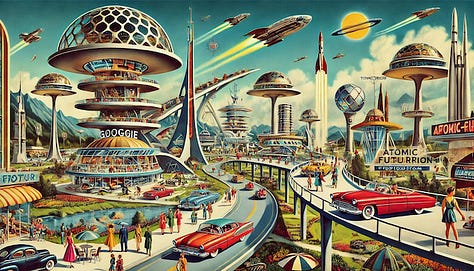

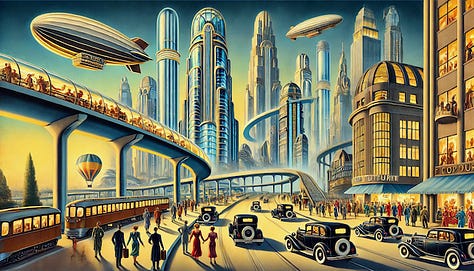

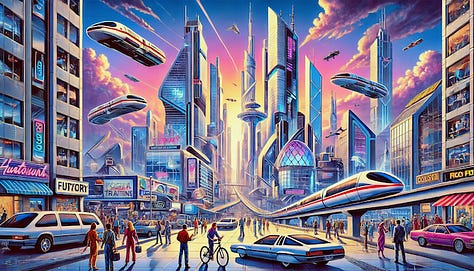

I asked ChatGPT to come up with illustrations for “the world of tomorrow” as imagined in the 1930s, 1950s, 1990s, 2010s, and today. My goal wasn’t to get an illustration for this post—I have more historically accurate images in my files.

Rather, I wanted to get some insight into what is in the AI training set, as an indicator of aggregated culture. In all images, “the future” is crowded, with a lot of cement and flying vehicles. Only the 2010 image has parklike open space, and it was one of two images offered, with the system asking me which I preferred. The other one kept up the pavement theme:

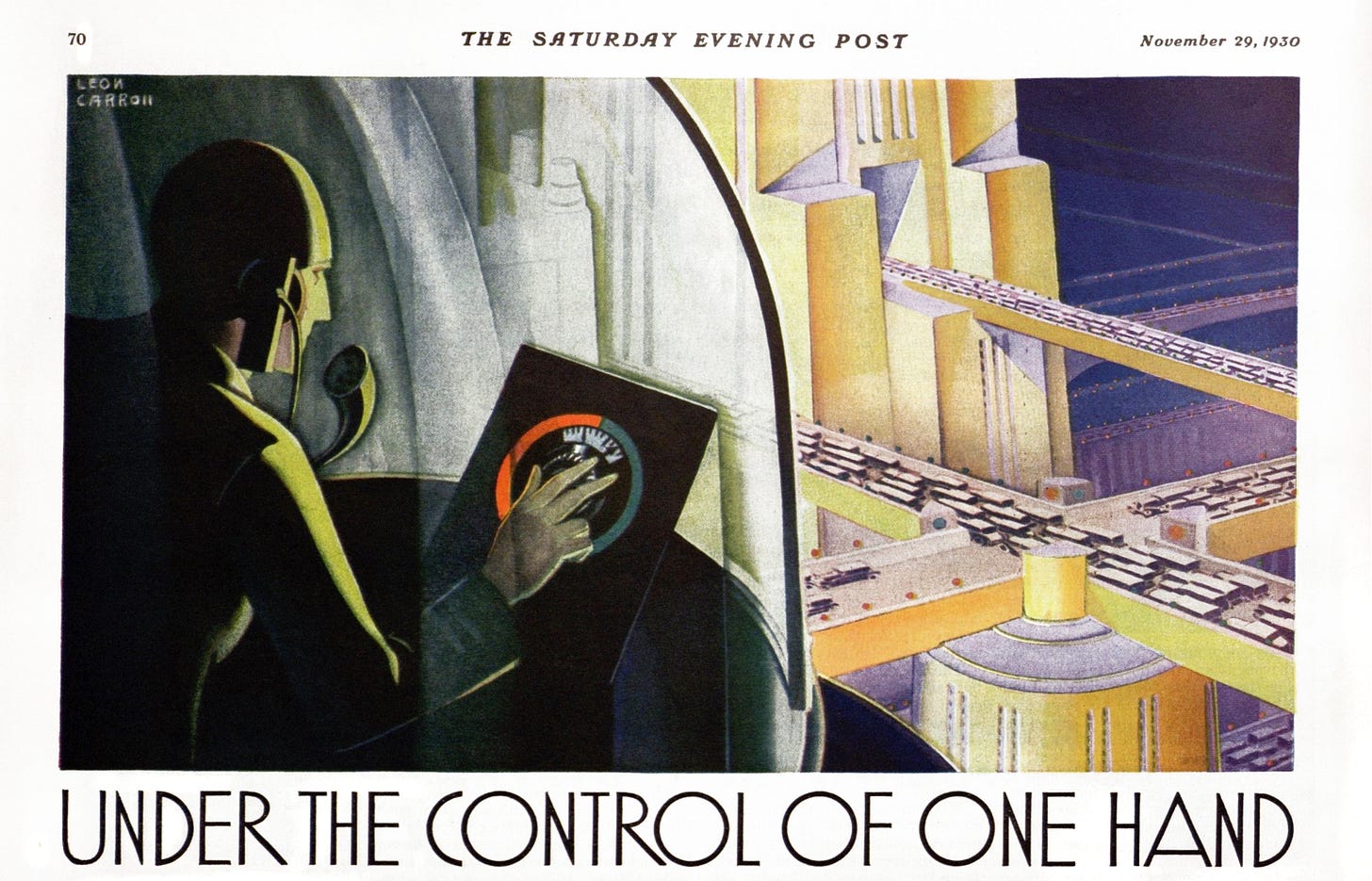

They do not show the future as experienced by an inhabitant but rather a God’s eye view. This is partly a function of the illustration’s requirements—the system is packing as much as possible into a single image—but I think it also illustrates an important cultural convention established in the early decades of the 20th century: the top-down planner’s view.

Here is a image that represented the future to moviegoers in the 1930s. To understand why, read the essay:

If you’ve never watched The Thin Man and its sequels, I highly recommend them. Great fun.

Next year, one of the most bizarre artifacts of 1930s future glamour will finally be in the public domain: Madam Satan, which features a costume party on a dirigible in which the entertainment includes an electricity dance. We’ve seen it a couple of times at American Cinematheque events and it’s not to be missed.

Futuristic Fashions and a Special Offer

Every few years people on social media rediscover this video, which is based on the projection of future fashions featured in the February 1, 1939 issue of Vogue, an Americana-themed issue with some previews of the 1939 World’s Fair.

While cleaning up yesterday, I discovered that, between glamour and textiles, I have managed to acquire two copies of this issue of Vogue, which sells for around $200 on Etsy.1 Click the first link for some photos of spreads. I would like to give the extra issue to a reader who would appreciate it. If you’re interested, please reply to this email or post a comment explaining your interest. I will give priority to paid subscribers with annual subscriptions.

Odds and Ends

I am booking speaking engagements for the first half of 2025. If you’re interested, please email me at vp@vpostrel.com. I do talks both in person and via Zoom.

I’m delighted to announce that my children’s book, Veronica’s Summer of Silk, will be published by Nancy Paulsen Books, an imprint of Random House. The title character is a 17th-century girl who goes to work with her aunt in the silk mill in Caraglio, Italy. I’ve finished the final revisions of the manuscript and we will begin discussing possible illustrators after the holidays. The book will be out in 2026.

I didn’t find a copy currently offered on eBay, which says something about the evolution of these sites.

The glamour of the future is back! Unfortunately it came back on Nov. 5 via the best friend of the guy who makes your hair stand on end, Virginia. But everyone really is grokking over that booster-catcher. It's wonderful and so much fun to watch on video.

One trivial example of why the retrofuture didn't happen is the flying car. We have flying cars, called helicopters. For reasons that could have been worked out in the 1950s, the idea of having one per family was never feasible, even assuming lots of technical advance. The air traffic control problem is just insoluble.

And that's true of other elements of retrofuturism - monorails, moving sidewalks and so on. There's no technical impossibility, but they weren't good ideas.

The escape clause for all of this was supposed to be space travel. The speed of light barrier would be broken, just as the sound barrier had been. The solar system and then the galaxy would be open to us. Now its clear that even a small moon base will be a massively expensive vanity project, and no other planet is remotely habitable (compared, say, to Antarctica). TWe have to take care of the planet we have, even if that means doing without a bit of glamour.