The Ethics of Higher Education

The American university evolved from three very different models, all of them threatened by two trends, one often critiqued by the left, the other by the right, but in fact complementary.

Highland Park United Methodist Church as seen from the adjacent SMU campus.

Earlier this week I had dinner with a small group of MIT professors from a variety of scientific disciplines. Among other topics, they shared their concerns about threats to the culture of free inquiry and the intellectual playfulness and audacity on which it depends. Whatever the form of threat—and they vary—these scientists worry that the institute is letting its concern for protecting its brand and pleasing government funders trump its dedication to scientific inquiry. In response, I recalled this talk I gave at a FIRE conference in, I believe, 2017. I’ve long thought I’d expand it into a “real article,” backed by more research, but never have. Until that day comes, I’m posting it here. (For more on FIRE, now the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, visit their website here.)

I am speaking this afternoon (Thursday, February 16) at Brown. Details here.

Two stories to start, one about academic ethics and intellectual safety, and the other about how strange an American university seems to a foreigner.

First story: When I was a senior in college, I took a graduate class in Elizabethan drama. When we got to the final paper, I had a big problem. The Christopher Marlowe plays that I found most interesting were already the subject of my senior thesis. I wasn’t inspired by the Shakespeare comedies that made up most of the other good stuff in the course and, while I liked Richard II, I had nothing interesting to say about it. The only play I found thought-provoking enough for a paper was The Merchant of Venice. That presented another problem: The professor had written a whole book about it. To make matters worse, I disagreed with his thesis, and even though it wasn’t exactly what I set out to write, once I’d read his book that disagreement inevitably became the subject of my paper.

I wasn’t trying to be obnoxious. I just didn’t have anything to say about the other plays.1

There are two problems with writing a paper disagreeing with your professor’s book. The first is that he has spent years, not weeks, thinking about the subject. He’s the expert and you are not. He will find every flaw in your argument and you won’t find every flaw in his. Plus he has a whole book to make his case and you have only a few pages. The second, of course, is that he could get mad and give you a bad grade just for disagreeing with him.

I worried a little about the first but not at all about the second.

Legally, the professor was free to give me whatever grade he believed appropriate. But I knew he would grade me fairly because I could count on his ethics as a teacher and scholar. I knew that his classroom was an intellectually safe place—not a comfortable place, not an undemanding place, but a place where I was free to disagree without punishment merely for dissenting. We would all put our feelings aside and make—and respond to—the best arguments we could.

“This puts me in a difficult position,” he wrote on my paper, before going on to comment on its substance. I had indeed put him in a difficult position, and he did still disagree, but he and his criticisms were reasonable and fair. He gave me an A-.

Second story: In 2005, someone at The Atlantic had the idea of sending the French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy around the United States in imitation of Tocqueville. One of his stops was Dallas, where I was living at the time, and I was his host for much of a day. At one point, we drove past Southern Methodist University, where my husband was teaching. BHL was puzzled by the idea that SMU would employ a Jewish atheist even for a secular subject like business strategy. “Why would the Methodists do that?” he asked.

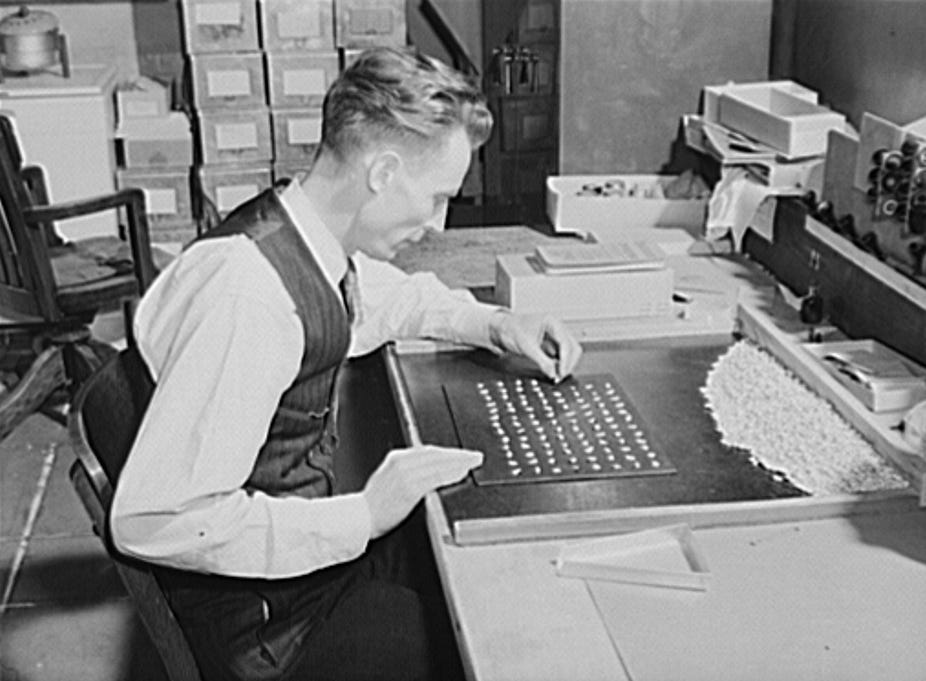

Character building, circa 1907.

The American university is a strange institution. First of all, it isn’t just one thing. There are nearly 5,000 institutions of higher education in this very large country. When we talk about “the American university,” we’re really discussing an ideal type: a place that combines teaching, research, personal development, career preparation, and social life.

That ideal evolved through the combination of three quite different models.

The earliest American colleges were devoted to civic and religious character development. They emphasized liberal arts, training future ministers and giving the Wall Street or law school-bound children of the wealthy a classical education. They also included that weird American institution, college sports, to inculcate self-discipline, leadership, and teamwork.

As the country grew, this model of higher education spread beyond the upper class. Many Christian denominations founded liberal-arts colleges, including schools for women. They believed that higher education improved individual character, made for better parents, and prepared Americans for citizenship.

The second wave of colleges were practical institutions, exemplified by the land-grant colleges that were funded by federal land sales in the mid-19th century. They trained farmers, engineers, and teachers. They also offered extension classes for local citizens who weren’t enrolled as students. They did research on things like crop rotation and hybrid corn. Unlike the private, character-building schools, they were largely government-supported and promised benefits to the citizenry at large, not just their student bodies.

The third model was a German import: the research university, devoted first and foremost to pushing the frontiers of knowledge and only secondarily to training students. Undergraduate education in particular was an afterthought. Johns Hopkins and the University of Chicago were early examples. While the practical colleges were rooted in the needs of their locales and the character-development schools were sectarian or clubby, research universities were cosmopolitan. They belonged to a worldwide community of scholars. The concept of academic freedom emerged from the research university.

Professor G.F. Sprague of the Bureau of Plant Industry at Iowa State counting seed samples of Iowa hybrid corn 1942. Library of Congress.

Most of today’s American colleges incorporate elements of all three of these models, which exist somewhat uneasily together. They suggest different purposes for the university and stress different ethical obligations on the part of students and faculty. All three are threatened, in different ways, by forces that manifest themselves in part through restrictions on freedom of speech.

One of these threats is the consumerist model of higher education. Another is a new form of character building that seeks to displace the liberal-arts ideal.

The consumerist model of higher education sounds perfectly reasonable at first, because it works so well for so many other things: I pay money and you make me happy.

This model treats higher education as a packaged experience, like a resort vacation, that includes an educational component and awards a certificate of completion. It encourages schools to invest more in recreational facilities, new dorms, and student-affairs administrators than in new faculty. It leads to much better food, with choices for every type of diet, and less taxing classes. It ignores the ethical obligations of students to study and learn and professors to set standards and reward excellence.2

And, to get to FIRE’s mission, the consumerist model inevitably encourages restrictions on free speech. After all, if the customer is always right, and students are the customers, then speakers and ideas that upset even a few students constitute bad customer service. Allowing Ann Coulter to speak on campus is like having the police drag a paying customer off a United flight.

The consumerist model dominates American higher education today. But it isn’t alone. One of the reasons our debates over free speech on campus are often so confusing is that it co-exists with a seemingly contradictory model: a new version of the old character-building ideal. The consumerist model has no political agenda. It’s an equal-opportunity censor that simply wants to keep student-customers happy. But by eroding the university’s mission to pursue and transmit knowledge—and the scholarly and teaching ethics that support that ideal—the consumerist model destroys its resistance to a more overtly political threat.

The new character-building ideal is specifically left-wing. It seeks to develop students’ sensitivity to issues of social justice and environmental crisis. Its adherents’ sense of right and wrong trumps their devotion to the advancement and transmission of knowledge.

Although some of these adherents believe in—or believe they believe in—the older liberal-arts ideal of critical inquiry, they tend to direct that inquiry outward, at American society, rather than inward, at their own assumptions. At best, they are like the good liberal Presbyterians who ran my parents’ colleges. They were happy to probe the ramifications of Christian teachings in the modern world but didn’t challenge the truth of Christ’s resurrection or divinity.

This moderate strategy can work in a relatively homogeneous environment, where basic assumptions are shared. But it can only tolerate so much dissent without cracking. And when it cracks, the school must choose between its allegiance to critical inquiry and its devotion to “higher truths”—between the pursuit of knowledge and the enforcement of doctrine. As their faculties and administrations grow more intellectually homogeneous, today’s campuses risk turning fundamentalist: allowing no more dissent on political questions—in the classroom or out of it—than Bob Jones or Liberty University permits questioning the inerrancy of scripture or the creation of the world in six literal days. When you limit the range of debate and forbid certain questions, you stifle the creation of knowledge and, over time, erode both the purpose of the university and the character of its constituents.

I wish I could end with a simple five-point plan for reversing these trends. One reason FIRE spends so much time on legal issues is that, in the short run at least, the courts are a friendly to free speech. So is much of the press. But, ultimately, protecting freedom of inquiry and the free expression essential to it depends on hearts and minds.

We, too, are in the character-building business. We are asking people to commit themselves to a vision of the university as more than a place to party or get your ticket punched—to treat it as a precious institution for the advancement and transmission of knowledge. That demands a lot more than a willingness to provoke the easily offended. It means trying and sometimes failing, challenging your beliefs, facing attacks, not knowing the answers, or even the questions, in advance. The process is satisfying in the long run but not always pleasant at the moment. It requires ethical commitments and the self-discipline to stick to them, even when you’re put in a difficult position.

In the classes I’ve taught at Chapman University, we’ve always had to develop prompts for student papers—something I don’t remember having either in high school or college. Here’s the final assignment for “Ambition and the Meanings of Success”:

Formulate a thesis inspired by one of the following topics. You may focus on a single work or draw on multiple sources to develop a broader pattern.

Your thesis must be something that could be wrong—that someone could against as well as for—not a factual statement. Saying, for instance, that Jiro’s success comes from constantly trying to improve his sushi is not a thesis. It is something the movie tells us is true. A good thesis will often answer the question why or it will establish a pattern out of disparate examples.

You may rely entirely on material we’ve covered in class or, after discussion with the professors, delve into other examples. If you would like to explore another topic, you may do so with permission. In all of the following, the questions are simply examples of avenues you might explore. There are many other possibilities.

Ambition over time: Most of the ambitious people we’ve discussed are in the early stages of pursuing their ambitions. There are three exceptions: Jiro, Norma Desmond, and Tennyson’s Ulysses. What are the challenges of aging for an ambitious person? How does ambition change with time? As a young person, what might you learn about ambition from someone significantly older?

Friends and partners: Few ambitious people succeed alone—or even try to. We’ve seen examples of productive partnerships and also of conflicts. In some cases, ambitious individuals collaborate as equals. In others, one person is clearly the lead and another, voluntarily or not, the supporter. We've looked at evidence that friendships with wealthier people can lead to upward economic mobility. Why might that be? When does collaboration succeed? When does it break down? What challenges does ambition pose to interpersonal relationships? How can those relationships further ambition? What might explain the connection between friendship and upward mobility?

Transcendent ambitions: Ambition often includes goals that go beyond fame or money. What are the pitfalls of “big” or “noble” ambitions? What are the advantages? If two people pursue the same ambitions in the same way but for different reasons, one transcendent and one mundane, should we evaluate their actions differently?

Finding your place: “Finding your place in the world” is usually a metaphor, but pursuing one’s ambitions often requires literally moving to a new location or environment. What kinds of places foster success? What does it mean for an ambitious person to find their place?

You might assume, as some conservatives do, that the “practical” model of higher education as job training is compatible with the consumerist impulse. But it is even more threatened by it. Keeping students happy erodes the demand to master material, leading to less course content and more generous grading. (Talk to anyone who has taught MBAs for more than a decade and you’ll get an earful.) When practical credentials are at stake, the consumerist model is especially corrosive.

This is fantastic. I would definitely read/buy the longer, more researched version. What I particularly appreciate is the emphasis on the higher education being more than one thing, which means that its problems or more than one thing. My biggest qualm on these matters is that progressives want to blame everything on the consumerism angle and on the failure of government funding to continue infinitely expanding. And conservatives want to blame everything on wokeness.

Out problems are multi-located. Our solutions must be the same.

Yes, please write a longer version. For many years I taught at a small private Catholic college--its strategy for survival was to build new sports fields, new dorms, a better cafeteria, and offer more sports teams. It kept offering new majors without the faculty to teach them.