Cresting a hill in eastern New Mexico, I saw, glimmering in the distance, what looked like a suspension bridge. But I was hundreds of miles from a wide body of water, and there was no platform for the shining cables to support. What I was seeing were high-tension wires carrying electricity. I was struck by the contrast. We consider suspension bridges beautiful—a proper subject for wall art and souvenir postcards. Electrical transmission lines are at best a necessary evil, at worst a blight on the landscape. Yet objectively they look similar. Why the different attitude?

A half-remembered passage from Paul Shepheard’s The Cultivated Wilderness came to me…something about cultivation as the work of humans in relation to the beauty of wilderness. When I got home, I looked it up:

The wilderness is not just something you look at; it’s something you are part of. You live inside a body made of wilderness material. I think that the intimacy of this arrangement is the origin of beauty. The wilderness is beautiful because you are part of it.

Cultivation—the work of humans—has a different sort of beauty. There is nothing else under the sun than what there has always been. Cultivation is the human reordering of the material of the wilderness. If it is successful, the beauty of it lies in the warmth of your empathy for another human’s effort.1

Cultivation—the work of humans…is the human reordering of the material of the wilderness. That was it.

It’s easier to perceive the human reordering of the material of the wilderness when natural processes are still obvious. Electricity cables crossing fields and ravines look more graceful than similar cables in the midst of urban sprawl—if only because you get an uninterrupted view of their curves. Yet such cables also overtly disrupt “nature,” which more often than not represented by cultivated farms, forests, or pastureland. I disagree that empathy for human effort is always the source of cultivation’s beauty—I’d argue that the power lines’ beauty was entirely formal—but it’s definitely one source.

As I drove through less-populated regions of the west, I was struck by how obvious it was how many people work transforming physical stuff. It’s partly what you see—farms and agricultural processing centers, oil wells and light manufacturing sites—but mostly what you don’t. Even hospitals are scarce. And you certainly don’t see the “For Your Consideration” billboards that dot my usual environs.

Flagstaff has plenty of brainiacs—and, according to an overheard restaurant conversation that appeared to follow a science department job interview, “it leans into nerd culture”—but even they need physical tools, notably telescopes. Albuquerque has the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History—a reminder of the region’s importance as a center for aerospace and defense work (and its history of uranium mines).

Long ago, I read that an important difference between environmentalists in the U.S. and the U.K. (or maybe Europe more generally) was that Americans tried to preserve wilderness rather than the cultivated countryside. We imagine nature as wild, free, and unpopulated. But, of course, humans have been reordering the material of this continent’s wilderness for thousands of years.

One of the Willa Cather stops on my trip was at Walnut Canyon National Monument, outside Flagstaff, Arizona. As “Panther Canyon,” this site plays a central role in The Song of the Lark, which Sean Crockett and I taught in our first-year seminar at Chapman University. While spending time there, the novel’s protagonist, Thea, finds her calling and her voice.

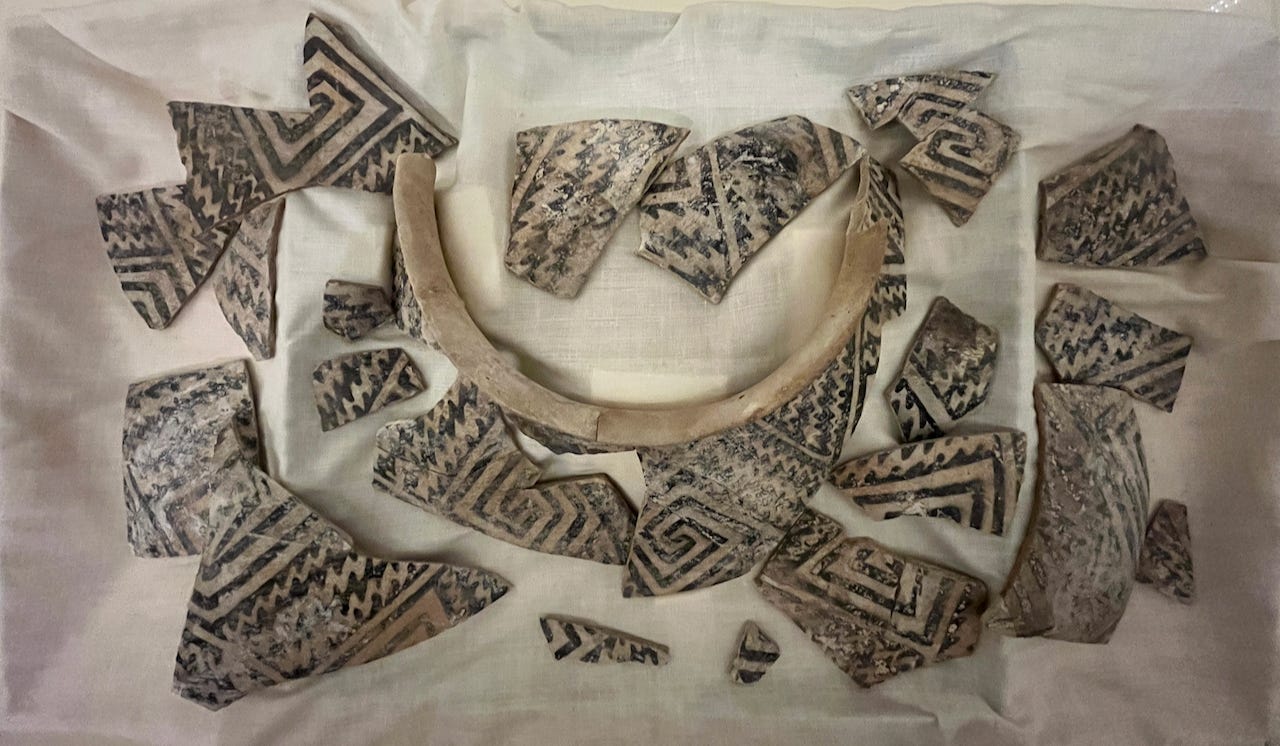

By geological accident, the sides of Walnut Canyon feature naturally carved out shelters, where softer rock has worn away, leaving solid floors and low ceilings. Ancient people settled on both sides of the canyon, adding walls made of rocks and clay. Eventually they moved on, leaving behind their dwellings and artifacts, notably decorated pottery. Today the pottery is in museums and visitors have to leave the park at night. But in Cather’s novel, Thea sets up her own little room and lives there.

Thea’s experience exemplifies Shepheard’s idea that the beauty of cultivation “lies in the warmth of your empathy for another human’s effort.” She identifies with the ancient people, particularly the women who made decorated vessels to hold precious water. They inspire her to pursue excellence in her own art.

Cather writes:

Nearly every afternoon she went to the chambers which contained the most interesting fragments of pottery, sat and looked at them for a while. Some of them were beautifully decorated. This care, expended upon vessels that could not hold food or water any better for the additional labor put upon them, made her heart go out to those ancient potters. They had not only expressed their desire, but they had expressed it as beautifully as they could. Food, fire, water, and something else—even here, in this crack in the world, so far back in the night of the past! Down here at the beginning that painful thing was already stirring; the seed of sorrow, and of so much delight.

There were jars done in a delicate overlay, like pine cones; and there were many patterns in a low relief, like basket-work. Some of the pottery was decorated in color, red and brown, black and white, in graceful geometrical patterns. One day, on a fragment of a shallow bowl, she found a crested serpent's head, painted in red on terra-cotta. Again she found half a bowl with a broad band of white cliff-houses painted on a black ground. They were scarcely conventionalized at all; there they were in the black border, just as they stood in the rock before her. It brought her centuries nearer to these people to find that they saw their houses exactly as she saw them….

All these things made one feel that one ought to do one’s best, and help to fulfill some desire of the dust that slept there. A dream had been dreamed there long ago, in the night of ages, and the wind had whispered some promise to the sadness of the savage. In their own way, those people had felt the beginnings of what was to come. These potsherds were like fetters that bound one to a long chain of human endeavor.

Thea decides to go to Germany to study opera and, by the end of the book, has become a world-renowned singer specializing in Wagner. Her ambition means leaving behind her own small-town past, including the family (her mother excepted) that finds her disconcerting: “The Cliff-Dwellers had lengthened her past. She had older and higher obligations.” The wilderness she cultivates is within herself, informed by the artistic efforts of those who came before her.

Thea becomes, as J.D. Vance would say, a childless cat lady (minus the cats). I leave to the reader whether that means people like her—or her creator—have no stake in the future.

In related news, archaeologists at Northern Arizona University have demonstrated that deep learning (aka AI) can classify potsherds as well as humans do. Here’s the paper (from 2021). We’re living in a golden age of archaeology in the Americas, thanks to new technologies like LIDAR that can penetrate forest cover, and AI promises to improve archaeological knowledge worldwide.

And if you’d like to try your hand at ancient pottery techniques, here’s a website to help you. The proprietor writes: “When I was a young man struggling to learn all I could about how to recreate prehistoric pottery, there were very few opportunities available to me because I could not afford to spend hundreds of dollars on a workshop. I would have loved something like AncientPottery.how back then. It is my hope that this website becomes a resource that artists use to learn new methods and that archaeologists use to better understand how ancient people made pottery.”

Odds & Ends (not necessarily hot off the pixels)

I bracketed my trip by seeing two remarkably appropriate movies, Horizon and Twisters. Interesting review-essay here.

The Abundance Institute features me and my ideas in a video.

I’m finally getting around to reading Steven Teles and Rob Saldin’s thoughtful essay at

on “the abundance faction.” This point can’t be made often enough:The state that America built in the 1960s and 1970s was, at its heart, regulative. From civil rights to environmental protection, its animating obsessions were things that it wanted to prevent from happening, such as racial and gender discrimination, nuclear disasters, highways through central cities, industrial accidents, dangerous toys, and environmental pollution. While much of this regulation was geared to private action, a great deal of it came to apply to the public sector as well. From the creation of compliance divisions inside of firms to the expansion of standing to sue to rules on public participation in government decision-making, the state that we created a half-century ago had the effect of displacing or slowing down the parts of organizations — public and private — focused on the delivery of goods and services. The aggregate effect of that state has been a widely diffused expectation that more or less everything that operates in physical space will take an extraordinary and unpredictable amount of time and be disappointing and uninspiring in its results.

Insofar as I belong anywhere politically, it’s with this faction. Although the immediate political future looks bleak, I continued to be excited by the increasing energy around ideas of progress and abundance. And if these topics interest you, I recommend reading The Future and Its Enemies, an oldie but a goodie!

Cool history and functional details of “inflatable amusements,” including bounce houses.

Sound-suppressing silk from the MIT lab of my textile buddy Yoel Fink.

Engineering skin bacteria to discourage mosquitoes. “The human scent is derived from the metabolism of the human skin microbiota. By knocking out the synthesis of key mosquito attractants, we pave the way for the development of a skin therapy that offers more permanent protection against mosquito-borne diseases." Faster, please!

From

(recommended!), a tribute to YouTube as a “learning machine,” focusing on sports techniques. YouTube is one of the wonders we’ve come quickly to take for granted. Information like this used to require in-person instruction.Please subscribe to my YouTube channel. Thanks to my popular videos on bandanas and calico prohibition I finally can get some of the money from the annoying ads. And I’m determined to make some more soon!

I used this passage in chapter 6 of The Future and Its Enemies. You can read the chapter as early Substack posts, starting here).

The quote from Paul Shepheard, "Cultivation—the work of humans…is the human reordering of the material of the wilderness" and your observations on it remind me of C.S. Lewis thought on domestic animals--summarized and paraphrased, that wolves are cool because they're wolves, but dogs are reordered, and kind of a fuller expression of, um, dog-ness because of their intentional cultivation.

Also, thanks for the news on engineering a mosquito-unfriendly microbiome, and sign me up.

That one paragraph you quoted from Teles and Saldin's Hypertext essay is by far the most congenial to dynamism. The rest of the parts that aren't about political strategizing read like a technocratic screed, one innocent of the last 100 years of thinking about incentives and information and the hazards of government planning. It sounds like Robert Moses envy, or Chinese Communist Party envy, or Woodrow Wilson envy, or FDR envy. (Even its historical understanding is distorted--we have plenty of historical memory recovery noting that the "needs of the time" that the Progressive movement was addressing were the dilution of the Northern European gene pool by swarthy immigrants, the undercutting of the wages of white native males by all others, the unleashing of productive energy by capitalism and technology to transform the economy, etc.) That they constantly talk of coalitions with "business" but never use the term "markets" is a warning sign about their vision, which seems to be less about permissionless innovation and private property and contract rights to build things than it is about empowering dirigiste bureaucrats to run transmission lines through your backyard in the name of amorphous climate change concerns.

The odd thing about the essay is that the one area where the national government ought unquestionably to be supreme--defense and foreign policy--gets zero mention. The problems of sluggish bureaucracy and inability to meet the urgent supply-side needs of the moment ought to be sounding a loud alarm bell in light of current events in supplying Ukraine, building our Navy back up to a size that can confront China and maintain our other commitments, etc. Our defense-industrial base is bloated and sclerotic and our service bureaucracies are failing to meet these challenges. Let's see the authors address that stuff before they start telling us about how enlightened national bureaucrats are going to save the economy and the rest.