Reflections on Burning Cities

I'm safe in Orange County, waiting to see what happens in the next couple of days.

I’m writing this from the one-bedroom condo we bought in Orange when I started my two-year Chapman fellowship. Since the fellowship expired I’ve been using it as a writing-podcasting-weaving studio and had planned to come down this week to do some writing. But I’d also planned to spend time last week at the Huntington Library in Pasadena, looking at centuries-old books. They haven’t been open since the day I had my appointment. Nature had other plans. (The library is safe.)

About 50 miles south from our home, our Orange apartment serves as a handy retreat from the fires as we wait to see what will happen once the winds pick up. Our home is usually safe from wildfires—as I always say, because we live in the concrete we only need to worry about riots—but with predictions of winds 45 mph to 70 mph starting tonight, embers could conceivably jump the 405 freeway and strike our neighborhood.

It can’t be said often enough that flying embers, not a wave of fire, are how these wildfires spread, making for some seemingly random patterns. The other day my nephew and his fellow carpenter buddies drove around northern Pasadena putting out small fires sparked by Eaton fire embers. He’s reportedly grateful for the asbestos shingles on the turn-of-the-20th-century fixer-upper he owns.

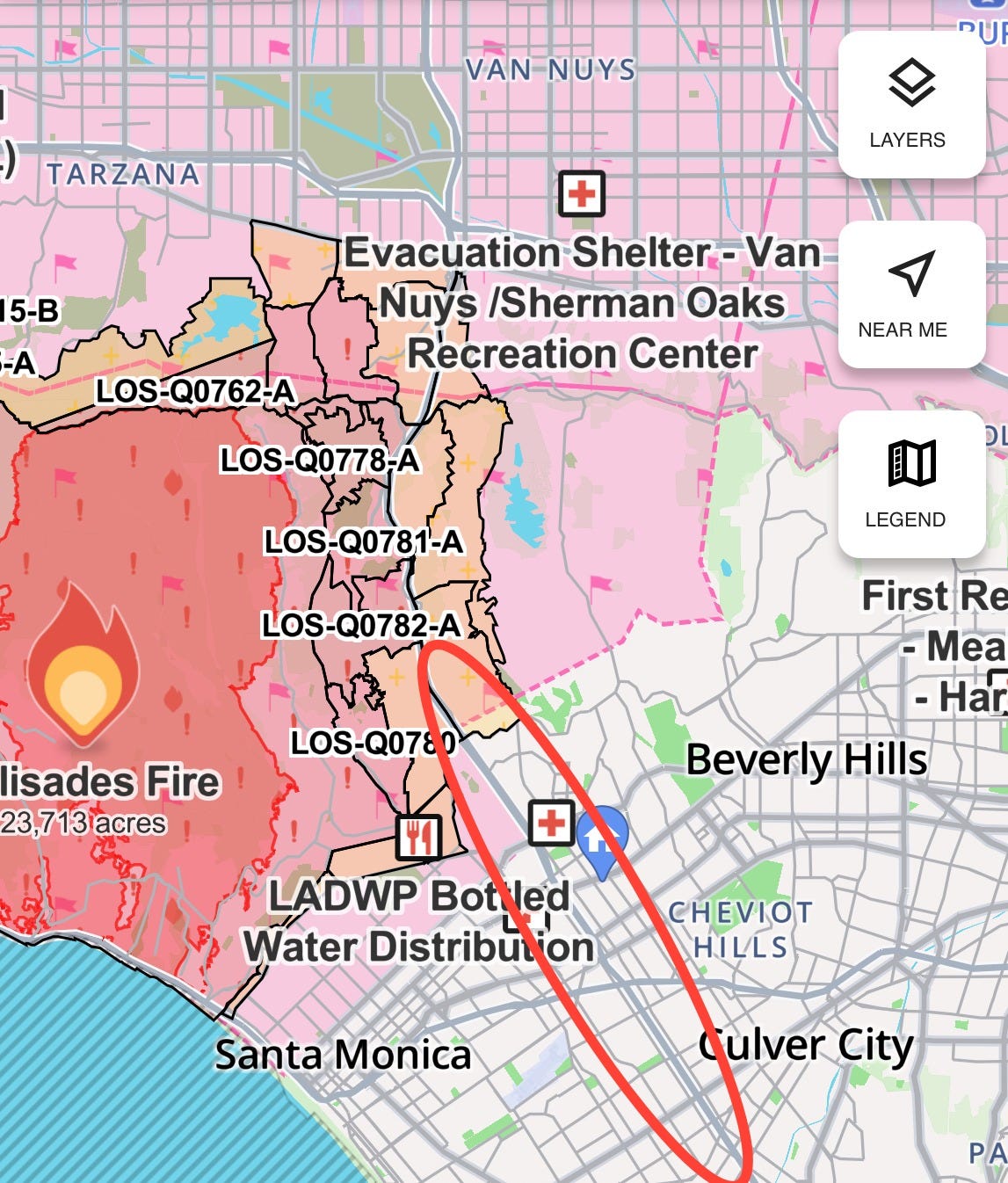

Above is a cropped screen shot from the Watch Duty app seemingly everyone in L.A. has now downloaded. A nonprofit enterprise inspired by its founder’s experience with a northern California fire, Watch Duty has proved indispensable over the past few days. Here’s a Hollywood Reporter report on its back story, posted today. Here’s an older, more substantial NPR story.

Less personal reflections follow.

Cities burn. Cities burn from from war and riots, from gas explosions and fallen power lines, from accidents and arson, from unattended stoves, bad wiring, bedtime cigarettes, and dry weather fireworks. Cities burn because fire is an essential tool of human civilization and one of its most dangerous. Fire is frighteningly powerful. Hence the myth of Prometheus.

Cities used to burn far more often than they do today. Writing in Works in Progress, Richard Williamson lists examples:

Boston, 1760. New York City, 1776. New Orleans, 1788. New Orleans, 1794. New York City, 1835. New York City, 1845. Pittsburgh, 1845. Toronto, 1849. Montreal, 1852. Portland, 1866. Chicago, 1871. Boston, 1872. Vancouver, 1886. Baltimore, 1904. Toronto, 1904. All of these are events in North American history that have the name Great Fire.

The rapidly industrializing and urbanizing United States chose timber as a cheap building material, which made the North America of the late eighteenth and nineteenth century especially susceptible to large city fires. But the major urban conflagration was hardly a uniquely North American phenomenon. Numerous European cities burned down several times; Tokyo and its antecedents suffered from a number of great conflagrations; Nero apocryphally fiddled while Rome burned in 64 AD, and the destruction of the Great Fire of London in 1666 led to the invention of private fire insurance, as well as the first organized systems of fire protection provided by those same insurance companies.

All of these fires destroyed large portions of cities, and in some cases almost all structures. It’s often remarked that cities were death traps of disease until advances in sanitation and medicine. But how frequently they went up in flames is less remarked on.

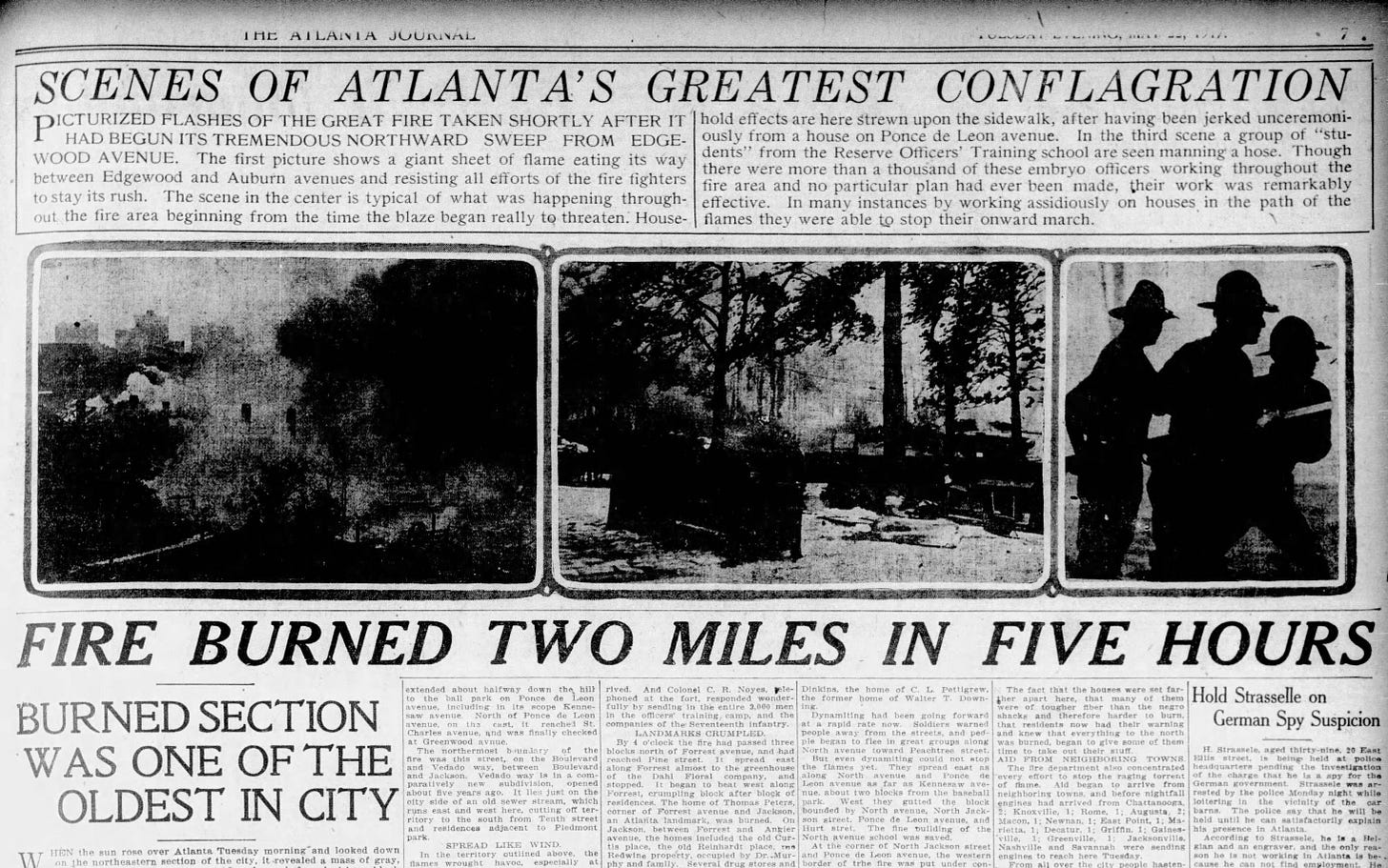

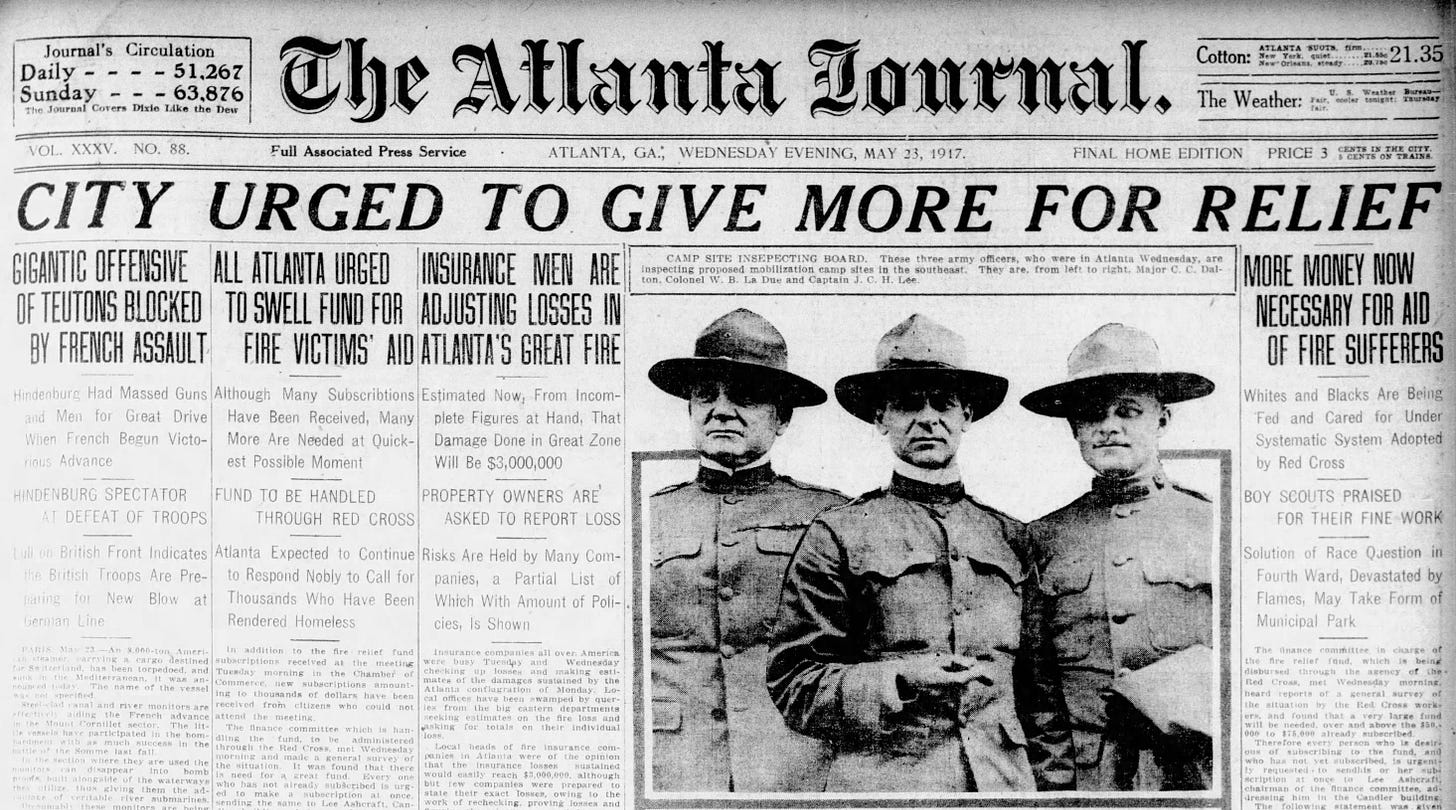

My grandparents told stories about Atlanta’s Great Fire of 1917, which they witnessed as children.1 Displacing 10,000 residents and burning 300 acres in the heart of the city, the fire briefly pushed aside headlines from the Great War. Dynamiting mansions in its path finally stopped its advance. In this 2012 article for Atlanta magazine, Rebecca Burns writes:

The Great Fire permanently altered Atlanta. The single-family homes near Downtown were replaced by apartment buildings that catered to the newly homeless—and the wartime surge in the city’s population. The development patterns along Boulevard, North Avenue, and Ponce de Leon are a direct result of the fire’s destruction.

The fire intensified the city’s segregation, as white residents moved to the north and east and black residents to the south. It also spurred improvements in fire prevention and fighting. According to the Atlanta History Center, “within a year of the fire the Atlanta Fire Department was completely motorized and an ordinance outlawing wood-shingle roofs passed in June 1917.”

A number of factors made urban fires less common: more electricity and fewer open flames for cooking and heating, new building materials and techniques, sprinkler systems, alarms, etc., etc., etc. All that prevention was expensive. To quote again from Williamson in WiP:

The total cost of fire today in the United States is estimated to be in the order of two percent of GDP, but that’s not because there is still a lot of fire. Actual losses due to fire constitute only 17 percent of that total, of which the vast majority is the statistical cost of death and injuries translated into dollars (in this particular estimate, the value of a statistical life is $9.6 million).

The remaining 83 percent constitutes the cost of fire protection and prevention, representing $273 billion in 2014. Of that, only $40 billion is the direct cost of fire departments. By far more of the expenditure is on indirect fire protection and prevention, like making buildings and products firesafe. These are crude high-level estimates (for example, the cost of making nonresidential buildings firesafe is assumed to be construction expenditure times 12 percent). But to give you a sense of scale – this is like funding an entire Apollo lunar program (estimated total cost about $280 billion in today’s dollars) every single year.

But it’s worth it, because the cities used to burn.

The fires currently raging in the Los Angeles metro area, inside and outside of the official city limits, will alter those numbers, as will whatever measures we adopt to prevent future devastating fires.

Virginia’s general rule of disasters: On the ground most people are exemplary and compassionate. On social media, the opposite.

When you’re waiting to see if your neighborhood is going to burn down—and hearing from friends and acquaintances who’ve lost theirs—you really, really, really do not need to see everyone jamming the fire into their favorite political talking points. Despite the demand, people shouldn’t be writing hot takes right now. You’re almost certain to be obnoxious and likely to be wrong. There will be plenty of time for fault finding later. Once the fires pass, what we’ll need is forward-looking constructive criticism. This could be the moment that California reclaims its can-do attitude, if only we don’t devolve into political squabbling.

For now, we need facts and explainers. The LAT has been doing an exemplary job of old-fashioned news reporting, the kind of well-sourced legwork you won’t find on Twitter. This roundup on The Dispatch, which includes on-the-scene reporting, is also quite good:

Why are these fires so destructive? One word: wind. The Santa Ana winds—strong, dry gusts that originate inland and sweep out over coastal Southern California—have caused blazes ignited by either power lines or humans to burn out of control. While Santa Ana winds are always strong, the system hitting Southern California last week was especially so, with gusts reaching up to 100 miles per hour. In such conditions, the Santa Ana winds work like a blowtorch for any fire that pops up. Even a relatively small conflagration can produce an “ember cast” that spreads flames into every available field source, said Rohde. “The embers work their way into small spaces of the attics, dead brush, and move into everything.”

National voices have been casting about in recent days for a key decision point or two that can easily be blamed for the fires’ extraordinary spread: misplaced priorities by state and local officials, the lack of controlled burns resulting in a buildup of fuel in wildlands, etc. While in retrospect there are steps local officials undoubtedly wish they had taken, there’s only so much that can be done to prevent blazes from spreading in a place with Southern California’s climate and population density.

Odds and Ends

The fire’s victims include a guy who won the $2 billion Powerball in 2023, as reported by the LAT.

If you’re in the area and want to help, here’s a Google doc showing needs for volunteers and donations. Dates are listed across the top and it’s frequently updated.

I have my own unpublishable hot takes, but I’ll save them for a later post.

When “urban renewal” was at its peak in the 1960s, my father used to cynically remark that it occurred because cities no longer had enough fires.

The ongoing agony for LA has a roadmap. It’s not pretty for those who want to return to normal ASAP. Insurance payments are designed to be drawn out and minimized. I’d love to understand how people can face this and solve for themselves, their homes and their neighborhoods.

LA Fires Revive Trauma for Homeowners Battling Insurance Claims https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2025-01-22/la-fires-what-to-know-about-filing-a-wildfire-insurance-claim

Here’s hoping your home—and you—stay safe. I can’t imagine. I grew up in Northern California in the country (six miles outside the city of Lincoln) and fire was a constant concern in the summer. My parents owned ten acres and keeping the grass down was vital. A neighbor a few lots down let his grass get out of hand on spring and mowed it too late. His mower blade hit a rock, threw a spark, and ended up burning the area for acres around.

We had to evacuate, though our house ended up being upwind from the resultant fire; we were fine. Dozens of neighbors were not. But fires like that pale in comparison to what you’re dealing with. The destruction is mindboggling.