Libraries of Stuff and Turbo Charging America's Tipping Craze

Newly published work, plus my history with the L.A. Times.

For Works in Progress I did a deep dive into the world of materials libraries, which are to stuff what regular libraries are to books. Here’s the opening:

Browsing the aisles at Material Connexion’s Manhattan headquarters can be overwhelming. The displays hold plaques exhibiting a seemingly random assortment of items: a perfume bottle, a shiny black grille, a square of denim, a vial of milky liquid, a scaly swatch of leather, a metal sphere. There are a couple of zippers and at least two toothpaste tubes, plus flooring samples, textile swatches, wall coverings, and assorted containers of mysterious liquids, chips, and powders.

What matters here is not each object itself but what it’s made of. The bottle is demonstrating a premium recycled glass, absent the common greenish tinge. The grille uses carbon fiber oriented vertically along the Z-axis, like the plush threads in velvet. The denim is polypropylene modified to make it dyeable. The vial contains latex rubber from the guayule plant. The leather derives from skins discarded by artisanal seafood cooperatives in Honduras. The sphere claims to be the first high-temperature dissolvable metal alloy suitable for the oil and gas industry. Who knew that fracking requires dissolvable parts?

This is a materials library – the world’s first, outside of small sample collections at architecture and design practices. Material Connexion was the brainchild of George Beylerian, a design enthusiast and serial entrepreneur. In 1990, he cocurated an exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt design museum called Mondo Materialis, inviting more than 100 architects and designers to showcase materials they were excited about. The exhibit served as what The New York Times called ‘a coming-out party for such materials as neoprene sheeting and electrochromic glass that could change color throughout the day’.

It also gave Beylerian a vision for a new venture. He would create a place where people could browse, handle, and borrow stimulating materials, a place where playing with material could spark new ideas and make unexpected connections. It would offer an organized and curated collection, independent from suppliers. It wouldn’t sell or broker anything, merely make commercial materials available. Patrons would pay membership dues for access. In 1997, Beylerian opened Material Connexion, calling it a ‘petting zoo for materials’. Along with the expected interiors-oriented crowd, early members included Mattel and Victoria’s Secret. ‘We liked the idea of opening the boundaries’, Beylerian recalled in a 2010 speech. Today Material Connexion encompasses some 10,000 items, with about 1,500 on display in its New York office and more in branches around the world.

Over the years, Beylerian’s vision spread. Universities, art schools, and other institutions established their own materials libraries, sometimes drawing on Material Connexion to help build their collections. The more the world went digital, the more popular materials collections became. Although most provide online databases, their core attractions can’t be reduced to words or pixels. To be understood, materials need to be experienced. ‘The samples are meant to be touched, hefted, inspected, and compared’, urges the website for Princeton University’s architecture and engineering materials collection, which opened in 2017. ‘Please come to the libraries and experience the samples in person!’

Like the open-stack libraries that first emerged in the eighteenth century, allowing members to freely browse the shelves, materials libraries grow out of intellectual enthusiasm. They represent new ways of communicating and organizing knowledge. They remind visitors that we live in a world of fascinating, mysterious, wildly varied stuff. Materials libraries are cool. They’re also practical, spurring individual discovery and cross-disciplinary exchange. Their spread suggests a decentralized way to boost material progress.

Read the rest here.

Sometimes I just write an article to get money. That was the motivation behind this LAT op-ed, making a point I couldn’t believe every chin-puller hadn’t already made:

If you left the U.S. for a summer vacation, you may have encountered a strange and refreshing custom: not tipping. Or at least not tipping everyone in sight.

Americans have long been among the world’s most profligate tippers. “We tip more occupations than any other country, and we tend to tip larger amounts than other countries,” says Michael Lynn, a professor of consumer behavior at Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration whose research focuses on tipping. “We’re kind of the tip-happiest country out there.”

Just wait. American tipping culture is poised to get even more intense. In a rare case of bipartisan agreement, presidential candidates Donald Trump and Kamala Harris both advocate exempting tips from federal income taxes. It’s a popular stance with many potential voters, notably in Nevada, a swing state whose many casino, hotel and restaurant workers rely heavily on tips.

The article was wildly popular with op-ed pages that subscribe to the LAT wire service. It’s been reprinted all over the country.

The pursuit of cash led to my original relationship with the LAT, back in 1992 when we were scrounging up closing costs for our condo.1 I wrote this piece on the foolishness of President George H.W. Bush’s proposal for a $5,000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers.2 The lead wrote itself: “President Bush’s $5,000 tax credit for first-time home buyers is a bad idea. I should know. I’m a first-time home buyer.”

Given Kamala Harris’s proposal for a similar $25,000 tax credit, the column is newly relevant. You can read it on my website here.

It was my second LAT column and developed into an informal publication rate of about a column a month. The op-ed page editor, Bob Berger, was an old-style crusty-but-benign newspaper man who appreciated my ability to fill the literal pink boxes on his wall chart—fulfilling his bosses’ demand for female writers—without forcing him to lower his standards. Without correcting for inflation, the fee the LAT pays for columns has actually gone down since 1992. But at least I’m house-rich. (Bush’s tax credit proposal did not go through and, of course, he lost the 1992 election.)

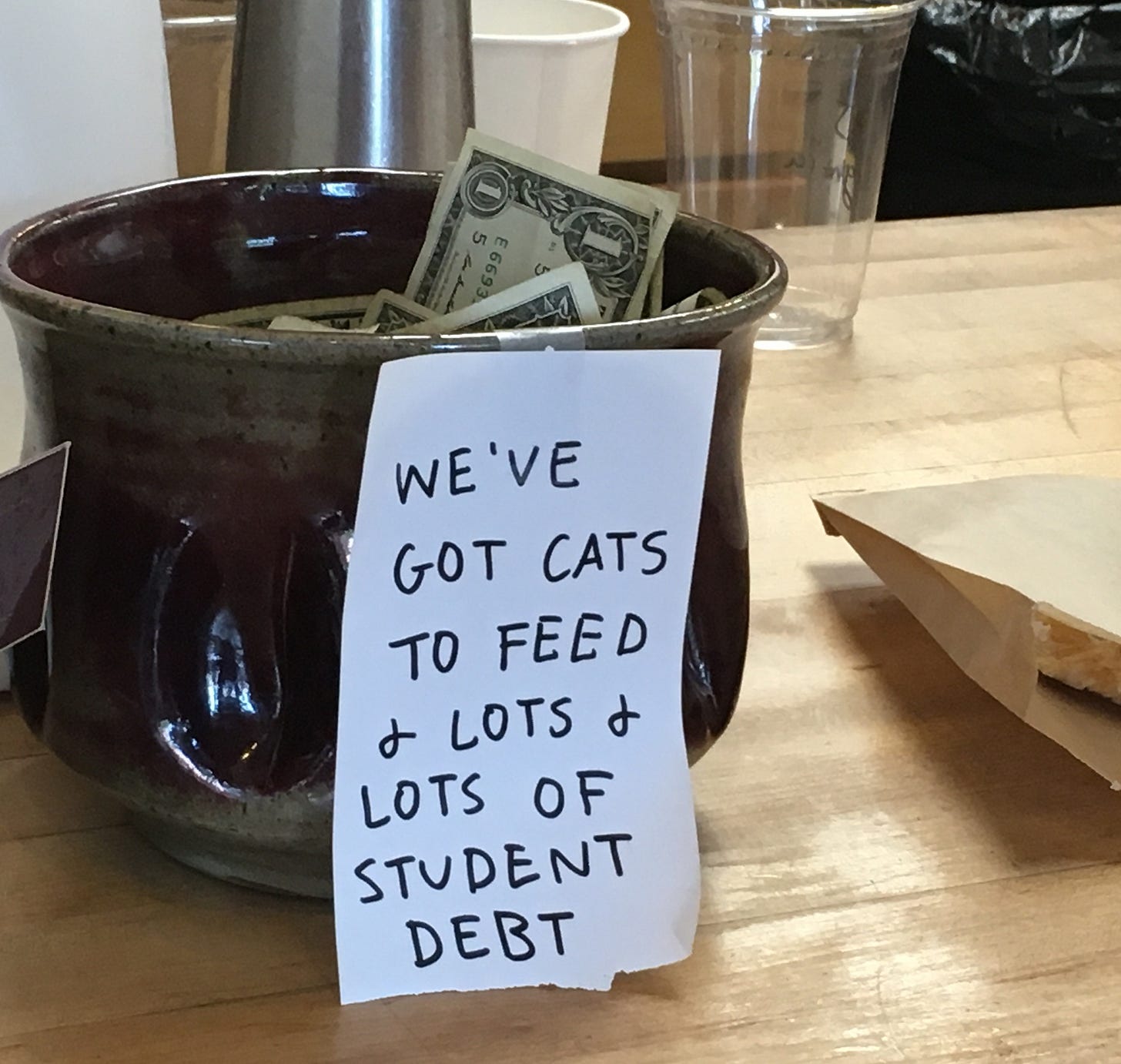

Speaking of tips, I’m afraid a paid subscription to my Substack doesn’t deliver a lot of extra value. But you can think of it as a tip to support my longer-term work.

Thanks for reading, sharing, and all your support.

The interest rate on our mortgage was 9.125%, plus private mortgage insurance because we could only come up with 10% down. Having come of age when interest rates were in double digits, we thought that was a pretty good deal. As we anticipated, the value of the place continued to fall, so we had to wait a few years to refinance when interest rates dropped. For good charts on the history of mortgage interest rates from the 1970s onward, visit this site.

Digging up this article made me realize that none of my old LAT columns are on my website. Fortunately the paper still has them in its archives so I can cut and paste. (I do own the rights.) Another project for the to-do list.

I remember Bob Berger. When I first submitted a piece to him (he accepted my first piece and nothing after), the people at Cato warned me that they called him "Mr. Personality."

The materials museum as "petting zoo" reminds me of your description of the GE materials facility (where clients could touch and handle interesting new materials that could be used for their products) in your book The Substance of Style.

TSoS is a great book. It was a required text for a large course on design culture that I taught at my U from 2004-2014.