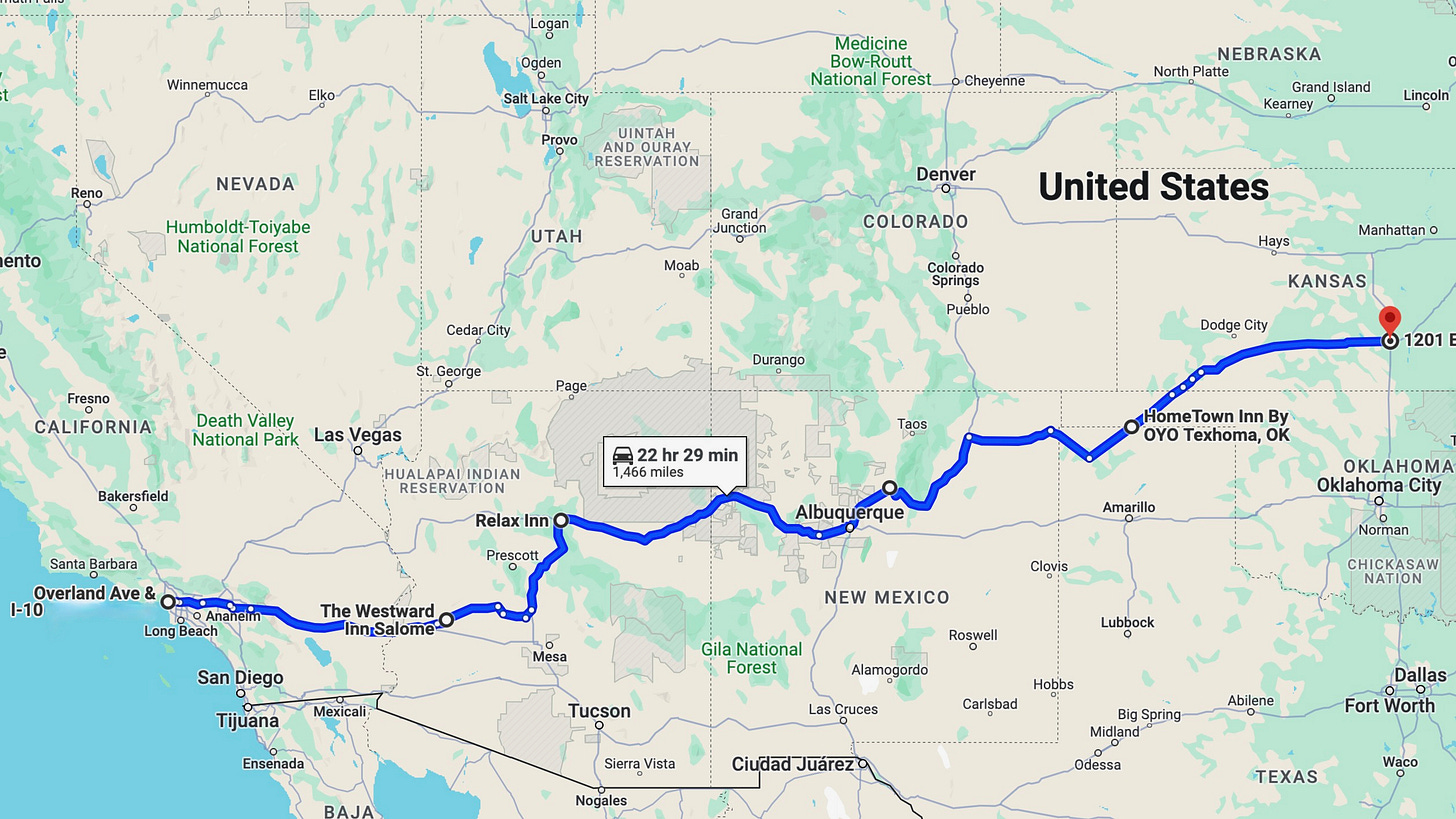

Last Monday, I set out from Los Angeles to drive to Wichita for the biannual conferences of the Handweavers’ Guild of America and the more mathy group Complex Weavers. I’ll be signing books, taking classes, joining a panel on “How to Add Fiber to Your Travels,” and generally showing the flag. Along the way, I’m making side trips inspired by Willa Cather’s work, which will be fodder for a future essay.

The trip lets me add Oklahoma1, Kansas, and (next week) Nebraska to the list of states I’ve visited, leaving only the Dakotas and Alaska for a complete set. (Speaking invitations welcome!)

This post’s title is actually inspired by my earlier trip to the Breakthrough Institute’s conference (from which I cross-posted Jesse Ausubel’s excellent talk). Democratic pollster Celinda Lake gave a presentation on climate-related messages that do and do not move voters to support Democrats and Joe Biden.2 The absolute worst message touted the plan to build 500,000 charging stations. While most poor messages had tiny positive effects, this one moved people toward Republicans. In particular, Lake said, women hate electric cars. They are terrified of being stranded. But they love hybrids.

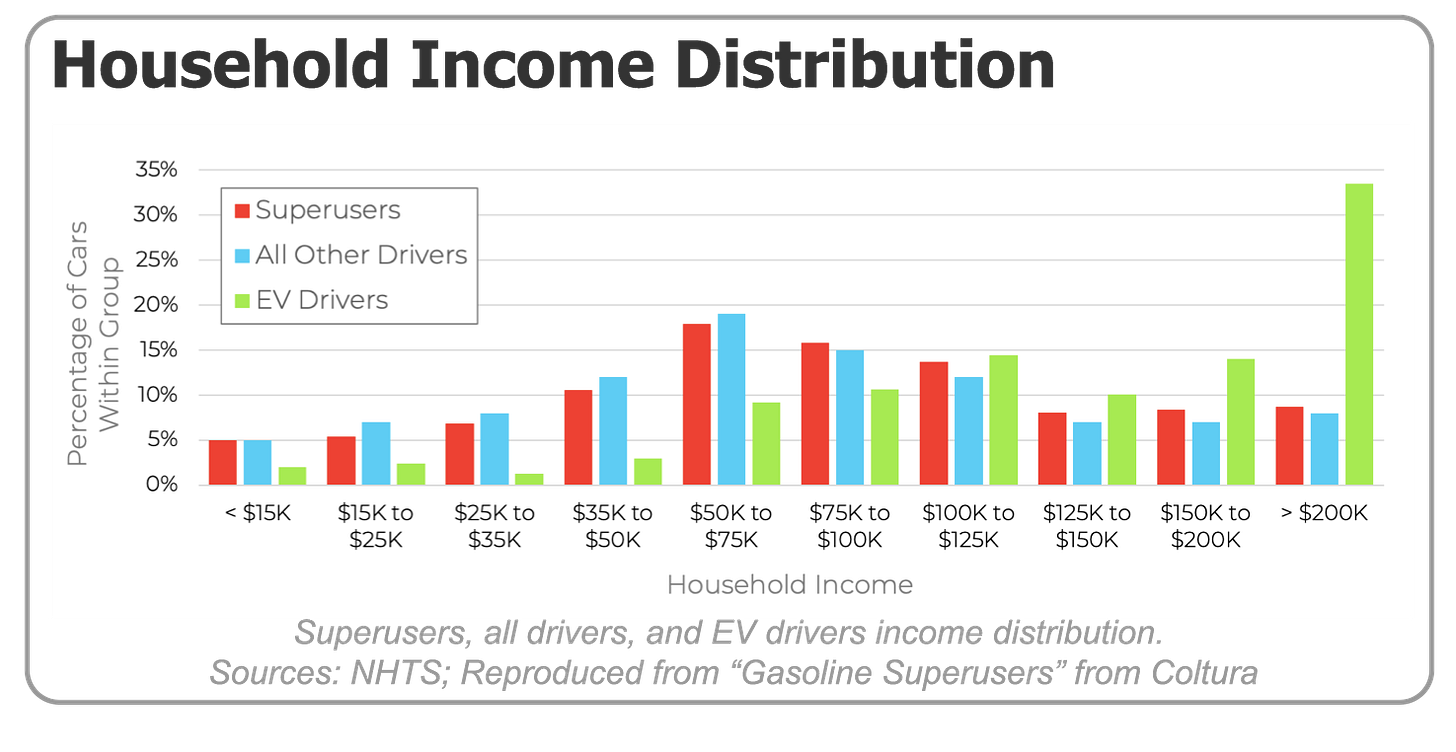

Toyota chairman Akio Toyoda has it right: Fully electric cars are not the answer. Climate policy that mandates EVs is making the ideal the enemy of improvement. People will just keep their gas cars longer—and if you think taking guns is politically hard, just try it with cars. EVs appeal almost entirely to people who have plenty of money and don’t drive much.

A contractor or gardener driving his truck around L.A. puts a lot more miles on it than a work-from-home screenwriter, but it’s the latter who’s going electric—even with gas prices that look good when they dip below $4.50 a gallon. (In Oklahoma and Kansas, I saw prices as low as $2.92!) EV purchases are motivated by a combination of ideology and tech lust.

I’m making my road trip in a 2018 Prius, which my mother gave me when she decided she was done with driving. Without it, I would have driven my 2003 Civic for another 20 years. It had 57,000 miles on it when I sold it. This one trip will double my annual mileage. It’s a reminder of just how impractical—not to mention expensive—electric cars are for most Americans.

1) This is a big, empty country.

I like to stop about every hour to stretch my legs, use the restroom, and replenish my drinking supplies. Thanks to truck stops, that’s rarely a problem. But in northern New Mexico, it was. I hit a stretch where there were ranches and farmland growing fodder crops, with houses distant from the road, but nothing else. Not a gas station. Not a store. Not a church. Nothing. Even trees were sparce. Finally, I hit Gladstone, thankful for the couple who runs the general store.

’s notion of One Billion Americans doesn’t sound crazy when you drive through the west.

2): American agriculture is capital-intensive and high-tech.

It’s well known that farming accounts for a tiny fraction of U.S. employment, 1.3 percent in 2021. (This paper provides a good overview of trends since 1969.) My drive took me through some of the most farming-intensive counties in the country, and I never saw anyone in the fields. In America, farmers don’t work the fields. Machines do. (See my early post on cotton harvesting.) Everywhere along my route I saw these machines, each as long as a football field, punctuated with heron-like legs: irrigation equipment, explained in this video.

3) A big country needs infrastructure to hold it together.

I needed roads to drive from L.A. to Wichita, along with gas stations, motels, and bathrooms. I took some food and drinks in a cooler but also frequented stores and restaurants, including a Mennonite-owned place in Texhoma called No Man’s Land Café. As I walked the couple of blocks from my motel, a guy in a pickup truck asked if I needed a lift. As I learned in my time finishing The Power of Glamour in the desert way outside of Twentynine Palms, in the boondocks people never assume you’re walking anywhere on purpose.

Once you get outside the cities, especially in flat, treeless territory, the infrastructure that holds the economy together becomes more apparent. Telephone lines parallel the road, often with railroad tracks beyond them. The highways are dominated by long-haul truckers. There are also many freight trains. Some carry the shipping containers I expected but others comprise specialized cars for ore, grain, or chemicals. Contrary to what many people think, the U.S. doesn’t lack trains. In an enormous country whose people can afford to fly, rail makes more sense for freight than for people. Most U.S. freight railroads have private owners.

Another form of vital infrastructure—high-speed internet service—is also provided primarily by for-profit companies. In rural areas, it can require space-age tech. (When I was working on The Power of Glamour in Wonder Valley, long before Starlink, I had a small satellite dish for internet.)

4) Traditional presidential campaigns force candidates and the reporters who follow them to see the country.

My trip is taking place amid the much-needed, possibly too-late, discussion of Joe Biden’s age-related cognitive and communication problems. I have opinions on that subject, which I’ll state in brief below. But the thought that struck me on the road is how depriving the Democrats of a real primary season means limiting them to a gob-smackingly parochial group of leading candidates—without even the finishing school of a national campaign.

As far as I can tell from her Wikipedia profile, Gretchen Whitmer has never left Michigan for longer than a vacation. Gavin Newsom—“a fourth-generation San Franciscan”—has never lived outside the Bay Area!3 Born in Kansas City but raised in the Philly area, Josh Shapiro looks positively cosmopolitan for venturing to upstate New York for college. Andy Beshear similarly left Kentucky for education in adjacent states.

There are as many Rhodes Scholars (Gina Raimondo, Wes Moore) on most short lists as there are people who’ve lived in multiple regions of the country. Raphael Warnock has lived in New York as well as Georgia and Alabama. J.B. Pritzker’s weird life of inherited wealth moved him from childhood in Silicon Valley, to prep school in Massachusetts, to college in North Carolina, and finally to Chicagoland (as the local media calls it) for law school and his career.

At least Kamala Harris has traveled the nation as a candidate and veep. That kind of travel doesn’t make you know the country, but at least you know what it looks like.

Finally, on the issue of the moment: The gaslighting no longer works. Biden is trying to run a campaign that depends on calling attention to Trump’s pathological lying. But his own campaign is based on a Big Lie about his obvious decline. The debate was the boy pointing out that the emperor has no clothes. As a NeverTrumper, I voted for Biden once. I won’t do it again.4 He may be less malevolent than Trump, but he has no more business in the Oval Office. His selfishness and his enabling wife are despicable.

It’s weird that I’d never been to Oklahoma, given that I lived three hours away in Dallas for seven years.

This was, of course, before his disastrous debate performance made his age problem no longer deniable. But the point would apply to any other Democrat.

Not that my vote in California matters. Democrats could win the state with a Biden corpse.

If you are going to be in Wichita, you must go to the NuWay restaurant on West Douglas. I think you get off at the Friends University exit. The NUWay was a new way to make hamburgers. The owner resisted offers to become a chain because he thought his loving technique would be lost. Enjoy the pretty much preserved original. Ketchup is now made available, but in the old days was not because he thought it an abomination.

What a wonderful piece, Virginia. It’s a book — and far better than JD Vance’s.