Why the Anti-Promethean Backlash?

Jason Crawford asked me a tough question. Could this chart hold an answer?

Roots of Progress Institute founder Jason Crawford recently hosted me at an Interintellect salon. Our topic was the relation between glamour and progress, inspired by my Works in Progress article. At one point Jason asked a provocative question: Why did the anti-Promethean backlash happen when it did? Earlier periods of technological and economic progress, he noted, had produced demands for more progress, not less. What was different about America circa 1970?

In the WiP article, I point to a combination of complacency among those who’d grown up amid postwar plenty and dissatisfaction with technocratic overreach. But why the complacency? Why not a demand for even more? My article didn’t consider that question.

Brink Lindsey, who coined the term anti-Promethean backlash, cites two possible explanations. First, “as economic security spread throughout the populace, priorities shifted from physical security and material accumulation to self-expression and quality of life.” Second, “as people acquired more, they had more to lose, and accordingly began worrying more about holding on to what they had.” The result was the backlash, defined as “the broad-based cultural turn away from those forms of technological progress that extend and amplify human mastery over the physical world.”

The first explanation entails a shift toward intangible experiences—lots of travel and dining out—and a turn away from the mass-market drive to “not bad” goods to everyone. That certainly happened. (I even wrote a book about one aspect.) But you’ll be hard pressed to detect low demand for physical security or less stuff in either election results or market trends. If anything, heightened concern for physical security, aka “safetyism,” is a major driver of the anti-Promethean backlash. As for loss-aversion, the empirical relationship to income is, as best I can tell, murky. My intuition is to think that if you’re on the material edge you’d be more loss-averse rather than less. But poor people do play the lottery more, so maybe Brink’s right. Either way, I don’t think his explanations fully explain the timing. Why 1970 instead of, say, 1950?

Megan McArdle recently took up the question from a different angle, inspired by reading Emily Post’s 1916 book about driving across America, By Motor to the Golden Gate, The condition of Post’s trip, often on heavily rutted dirt roads, were horrendous. But Megan was most struck by “the incredible optimism and wild ambition that runs through Post’s America. The Midwest, particularly, seems to be in the middle of a youthful growth spurt, with cities springing up out of the prairie full of vim and vigor and plans for the future.” (Emphasis added. I will return to this point.)

Our longing for that lost sense of optimism, Megan argues, shapes contemporary politics. On both left and right, activists “are asking why we can’t recapture the spirit of an age when America felt young and hopeful and capable of doing extraordinary things.” The reason we don’t feel that way now, she suggests, is that we’ve been too successful. Indoor plumbing is exciting when you get it, a third bathroom nice but not life-changing. The same is true for highways, bridges, railroads, and dams.1 “The political trade-offs are now harder, because we’re chasing incremental improvements, not life-altering change,” she writes. Youth, hope, and extraordinary achievement belong, in this gloomy analysis, to developing countries, China in particular.

I’m more optimistic, because Jason’s question pointed me to something I hadn’t previously considered. My first instinct, as a student of English literature, was to say that Jason was wrong. The 20th-century anti-Promethean backlash wasn’t unique. The Industrial Revolution generated one as well.

Victorian England produced many influential writers and artists, including John Ruskin, William Morris, and Augustus Pugin, who deplored modern industry and promoted an idealized medievalism. Their ideas left a permanent mark on intellectual life but had little immediate effect on the pace or direction of industrial change.2 Medievalism sold as a style but not as a political agenda.3 Its legacies were primarily aesthetic, realized in Gothic revival architecture, Arthurian poetry, pre-Raphaelite painting, and the British Arts and Crafts movement. The social criticism that actually transformed Britain demanded more for working people—political power and material abundance for the masses, not a return to feudal roles or an end to factories and machine-made goods. As long as a significant proportion of the population lived in material deprivation, the salient debates were over how to distribute the fruits of Promethean industry, not whether that industry was a good idea.

Besides, Jason wasn’t asking about the Old World. The United States lacked even Britain’s intellectual backlash. Americans who objected to industrial progress remained niche players, idealizing the ante-bellum South.4 There was plenty of dissatisfaction and conflict, of course. We had labor strife and muckrakers; socialists, anarchists, and populists; Edward Bellamy and the National Grange. But medievalism was confined to wallpaper and architecture, often installed or financed by industrial magnates. Feudalism wasn’t on the American agenda. What was different here? And what might it tell us about 1970?

As I talked to Jason, several things suddenly came together: the Old World vs. the New, multiple conversations with young people at the Progress Conference, and a passage from Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark:

She had often heard Mrs. Kronborg say that she “believed in immigration,” and so did Thea believe in it. This earth [the midwestern prairie] seemed to her young and fresh and kindly, a place where refugees from old, sad countries were given another chance. The mere absence of rocks gave the soil a kind of amiability and generosity, and the absence of natural boundaries gave the spirit a wider range. Wire fences might mark the end of a man’s pasture, but they could not shut in his thoughts as mountains and forests can. It was over flat lands like this, stretching out to drink the sun, that the larks sang—and one’s heart sang there, too. Thea was glad that this was her country, even if one did not learn to speak elegantly there. It was, somehow, an honest country, and there was a new song in that blue air which had never been sung in the world before.

That’s the spirit of the midwestern growth spurt, of “cities springing up out of the prairie full of vim and vigor and plans for the future.”

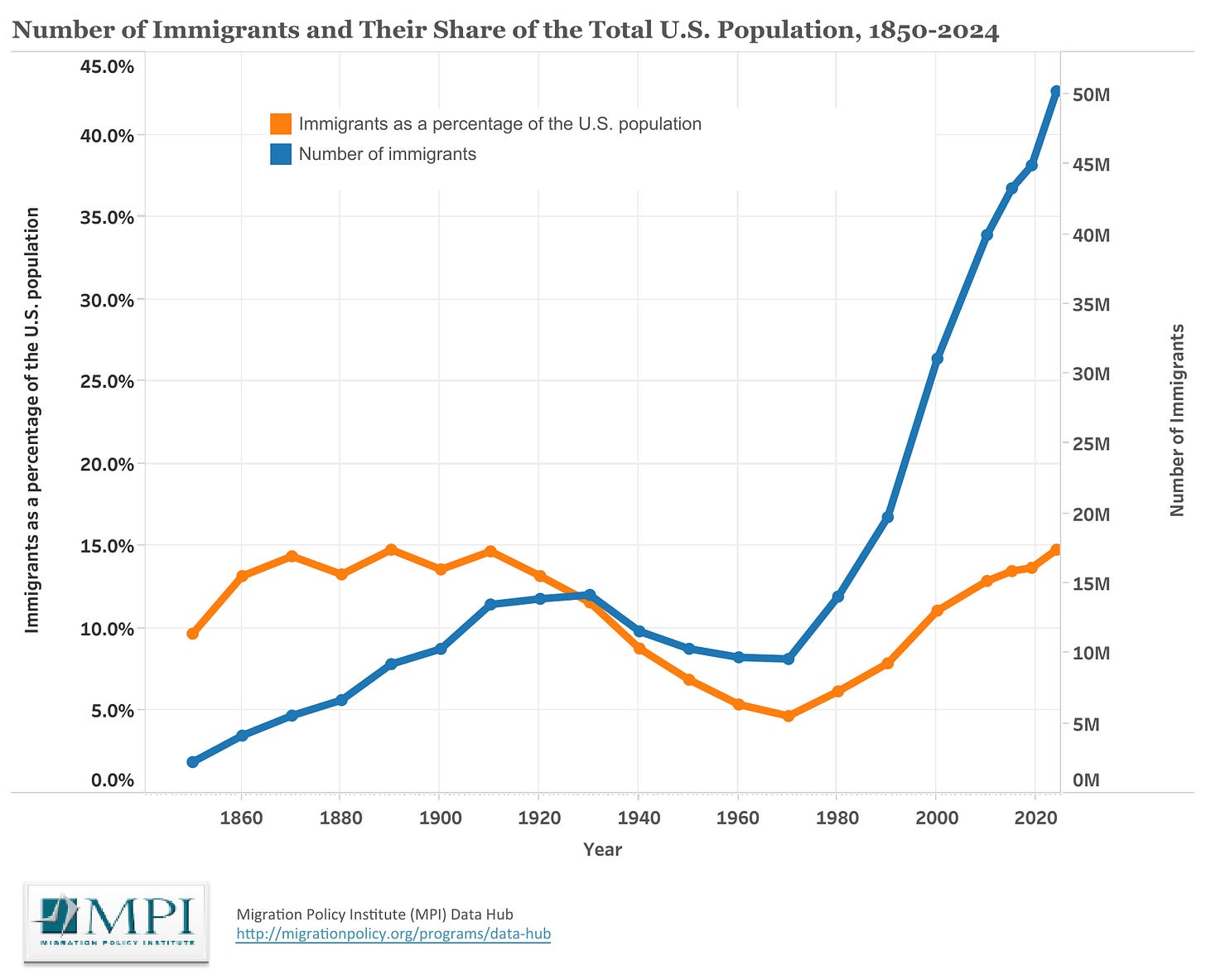

I did some mental arithmetic and suggested a hypothesis. The young Americans who proved so receptive to anti-Promethean ideas in the 1960s and 70s—those born starting from the late 1920s onward—weren’t just richer than previous generations. They were the products of the country’s four decades of restricting immigration. Instead of an America renewed by people looking for another chance, they had grown up in a more complacent society. These immigrant-deprived generations were much more likely than earlier generations to embrace and amplify anti-Promethean ideas, providing a mass of public support.

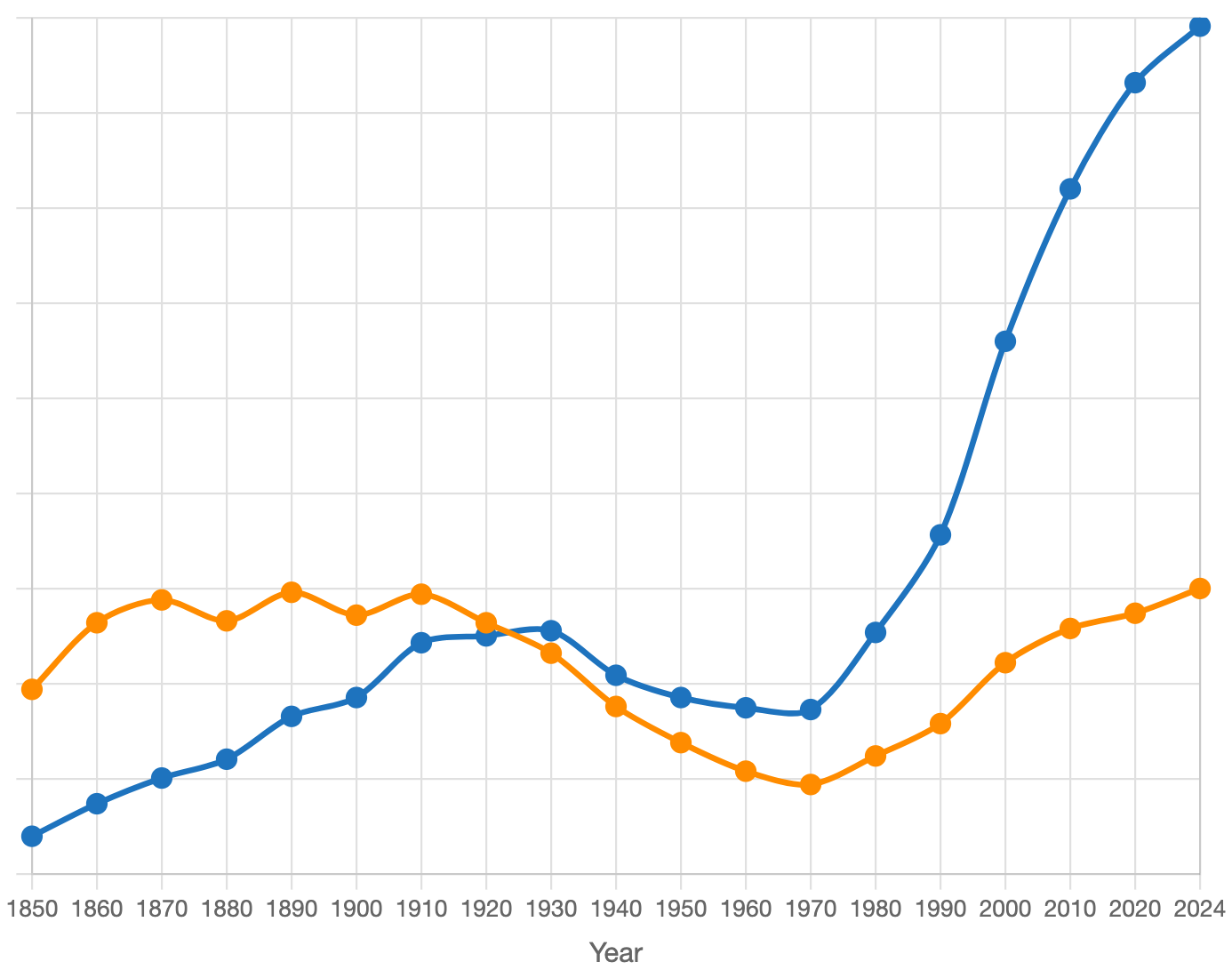

Later, I found remarkably congruent statistics. Nineteen seventy marked was the first Earth Day.5 It was also the year in which the percentage of the U.S. population made up of immigrants reached its nadir, with the total number of immigrants at the lowest point in a century.

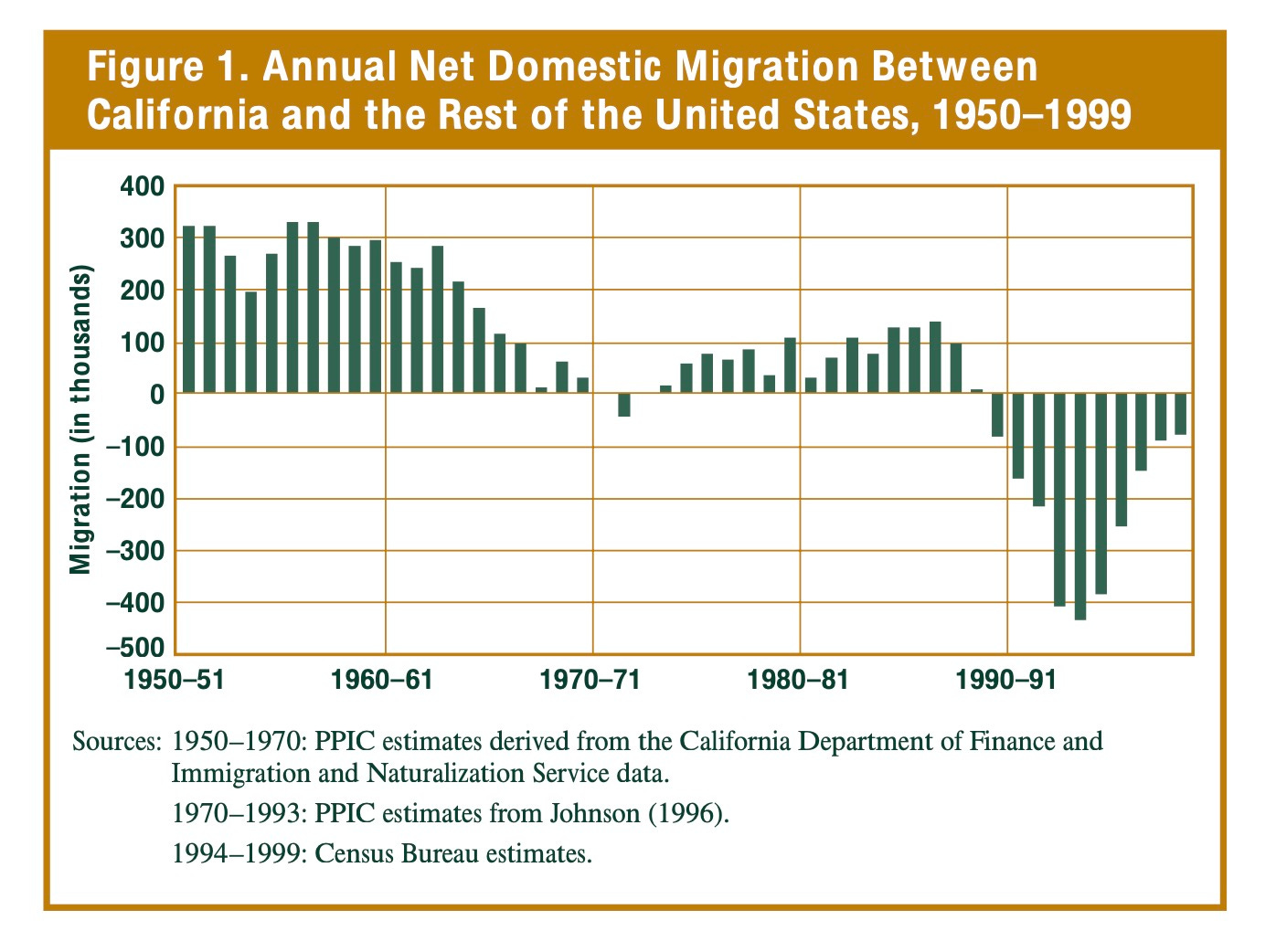

Internal migration, which surged after World War II, had declined as well. The “Second Great Migration” of blacks from the South ended around that time. Domestic migration to California, arguably the vanguard of the anti-Promethean backlash, peaked in the late 1950s, then declined significantly, occasionally turning negative. The resurgence in the 1980s, which was accompanied by large-scale international immigration, set off a “growth control” movement that resulted in new building restrictions.6

The anti-Promethean backlash arose when America was most like a normal, settled country rather than a nation of strivers seeking a better life. It intensified when the people who accepted the more static America tried to preserve it by legally restricting “human mastery over the physical world,” from power plants to housing construction.

My unscientific observation is that the progress and abundance movement is full of the children of immigrants. We seem due for a turnaround.

Recommended reading

Subscribe to the print edition of Works in Progress! It’s beautiful and I’m writing a regular, print-only column.

Creative Frontiers: a great new Substack from historian/musician John Hardin of the Abundance Institute. This post on how Duke Ellington used the microphone to create a whole new sound is fascinating. His latest is on AI-generated music and The Chipmunks. Check it out.

“The Middle-aged Millennial,” a delightful short tale by Naomi Kanakia whose opening explains its literary inspiration: “One day Rajiv woke up and realized that he was in a Cheever story!” I haven’t read Cheever but I have a feeling I prefer Kanakia. The story’s ending is surprising, funny, and wise.

Using similar reasoning I argued in this column, inspired by the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, that “World’s fairs are designed for people from homogeneous cultures who are still impressed by electricity.”

Medievalism did, however, inform some of the anti-Promethean backlash of the 1960s and 70s and is enjoying a resurgence on the anti-liberal right, particularly among Catholic integralists.

In a separate “From the Archives” post, I am reprinting a section from The Substance of Style in which I discuss neo-Gothic architecture and dreadlocks as parallel examples.

The Southern Agrarians of the 1920s and 1930s were the most noteworthy example. Although they lost the battle against the New South, more recent writers, including Wendell Barry on the anti-Promethean left and Sam Francis on the anti-liberal right continued their legacy.

This interview with Denis Hayes, co-founder of Earth Day with Senator Gaylord Nelson, is quite interesting: “The country was very ripe and ready for something like this. But campus teach-ins turned out not to be the place to start. The first thing that we did was find some regional organizers and send them out to colleges across the country. This was all starting the first week in January [1970]. And everybody came back after a week or two and said, “This is like running into a brick wall. This is not something activist students care about.” So we analyzed the mail that had come into Nelson’s office as a result of press coverage of his speeches. Overwhelmingly, it was from women, mostly they were 25 to 35, mostly college-educated, mothers of young children, mostly in single-wage-earner families, and they want to know what they could do to get involved.” Also, “ur biggest supporter by far was the United Auto Workers. We would have these floods of mail after we got something placed in a magazine. In the end, we got the United Auto Workers to start printing our newsletters for us and paying for our postage.” Why the UAW was so keen on Earth Day isn’t explained. There’s also some good stuff on Nixon and the EPA.

See my column “How I Caused California’s Housing Crisis.”

Interesting story.

But imo it doesn’t pass the smell test. At least as *major* explanatory factor.

Because the people who are on average more anti-abundance are the more highly educated, on average less anti-immigrant left.

Where - populist and nationalist and more positive on tariffs and international trade restrictions notwithstanding - the on average more anti-immigrant right is generally much more favorably inclined towards economic progress. In both its pre- and post-Trump versions.

Of course, my argument is that the lower middle class writ large isn’t as racist and anti- immigrant as elites (left, center and right) portray them so much as they are deeply anti-illegal immigration. There is of course a notable minority who are indeed racist and anti-immigrant, period, but that tail is not wagging the dog on the right (again, despite leftist media claims to the contrary).

The much simpler, more logical answer is that the anti-progress movement has come from leftist socialism/Marxism/environmentalism (the last where so many of the leftist socialists and Marxists went in the 70s and 80s and 90s as it was clear that neoliberalism / capitalism had won on the pure economic front), and more and more taken over the culture from its friends in academia, the media and Hollywood.

Open socialism has only shown up in the mainstream U.S. left since 2016, but the environmental movement you cite as a key source was where leftist energy was then, but is no longer exclusively the source of anti-abundance energy on the left.

IMO unlike the story that elites prefer to tell, populist nationalism and even anti-immigrant sentiment are at most an adjunct to the anti-abundance, anti-progress situation we have in the U.S.

The major truth is that the U.S. left and its leadership have abandoned abundance and economic progress. Narratives that don’t address that truth head-on are unlikely to succeed. And seem to me more like the case of the person who lost his keys in the unlit dung field preferring to look for them in the unlit parking lot, because it seems “less icky” over there.

I don't think immigration has a lot to do with it. It's more about whether economic growth and innovation have been making people's lives better or worse on the balance. The industrial revolution increased the supply of goods, but most people led more miserable lives until political violence and protest forced the ruling class to share some of the goodies. 20th century industrialization produced even more, but its centralization, political power, militarization, pollution and the like produced new problems that were addressed somewhat in the 1960s and 1970s. Now we have the internet and AI revolutions that offer so much but produce wretched, demanding jobs and crappy products with no user recourse.

Productivity may have increased, but very little of it led to improved living conditions. GDP per capita may have increased by a factor of three since the 1980s, but the value of an hour of labor in those terms dropped to one third. You have to be dumb, blind and stupid to think that the AI being rammed down one's throat at work is going to get one an iota of a better life.

It was one thing when Prometheus gave man fire, but it was another when he started setting the world afire.