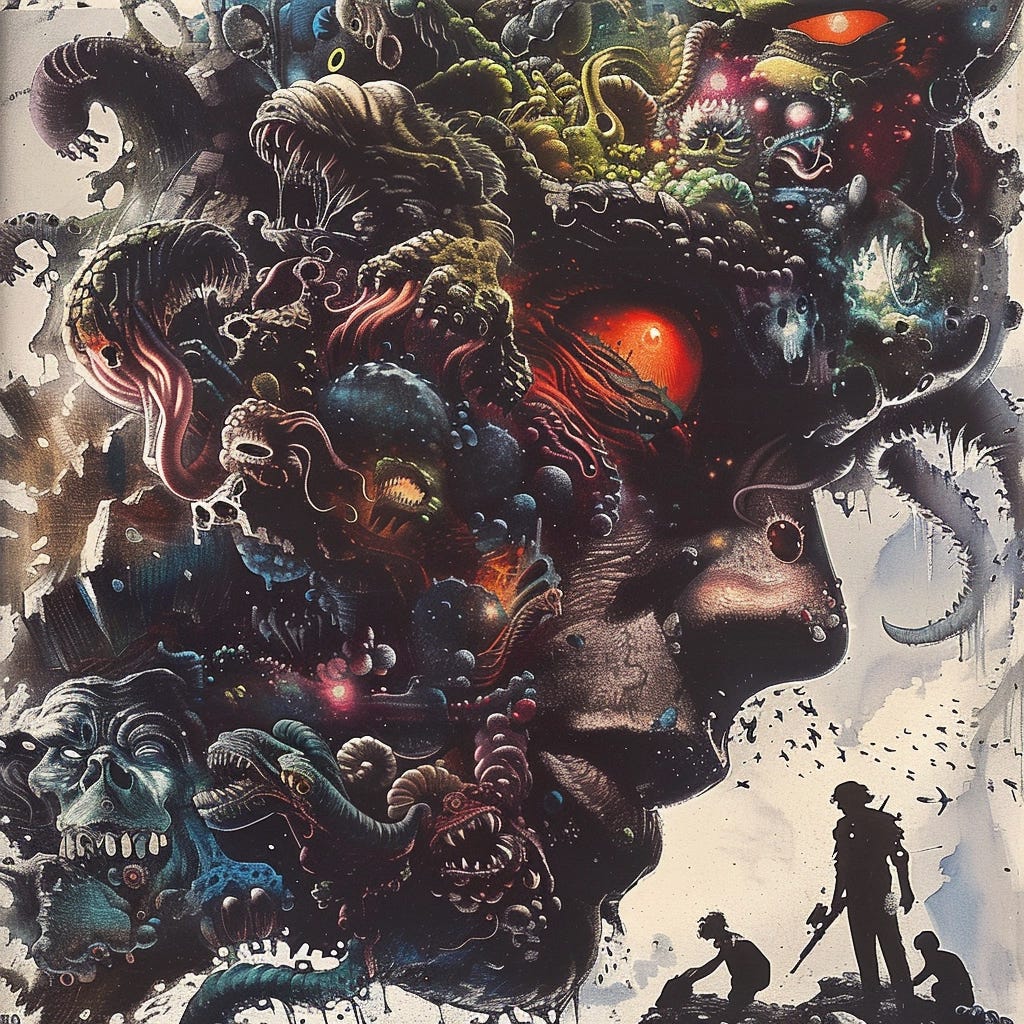

TMI and Monsters from the Id

A theory of why Americans are wallowing in self-pity and voting for bad character. Plus, I talk textiles and foreign affairs—and an expert defends my horrible speaking voice.

My friend and former Chapman University colleague John Thrasher recently introduced me to the concept of pluralistic ignorance. This is a social science term describing situations in which individuals know their own thoughts and behaviors but assume most people are different, when in fact they aren’t. The classic example is college students who don’t drink that much themselves but assume their classmates are always getting drunk, when those others also drink moderately.

John’s twist is to suggest that the breakdown of pluralistic ignorance explains the recent erosion of political and social norms of behavior—an erosion so extensive that “conservative Christians” who once upheld traditional norms of propriety in family and business life now avidly support Donald Trump, who is proud to be an unscrupulous operator and a serial adulterer.

John and I originally discussed his idea in conversation. He later sent me an email elaborating:

Typically, the idea of pluralistic ignorance (PI) is used to explain how pernicious norms or conventions persist despite their bad effects. The college drinking example is one. Another is Gerry Mackie's explanation of [female genital mutilation] in Africa. However, socially good norms and customs can also persist through pluralistic ignorance. An example that got me thinking about this was reports of Boomer grandparents being less involved in parenting than in earlier generations (one example here). Aside from stereotypes about Boomers just generally being horrible, my thought was that social media allows grandparents to publicly seem like they are more involved in their grandkids while actually not being very involved (e.g., posting photos, liking photos from their children, etc.). They can also see their grandkids on FaceTime or Zoom regularly; actually watching the grandkids is nice, but it is very costly in terms of time and energy.

Other customs and norms that constitute being a decent human being are also like this. People have never wanted to conform to these norms, but they believed that everyone else was conforming to them and expected them to as well. Social media shows us that most people don't have that expectation, and the conformity rate to many norms is much lower than we expected. We thought that everyone was more decent and norm-following than we were, but social media punctured that PI balloon. We got to see behind the curtain and realized that no one was really following the norms or expecting that anyone else was either.

I think this is a general explanation for the casualization and vulgarization of our culture that goes beyond social media. The aspirational middle-brow Americans of the past (which I think no longer exists) didn't really like opera, classical music, ballet, classic novels, or whatever. However, they thought liking such things was constitutive of good taste, and they believed that other people also thought that. They weren't good Christians, but they assumed everyone else was, so it was important to keep up appearances. The general expansion and democratization of media started after the war. They massively accelerated with social media and the internet, showing that no one cared about appearances, or at least the old ones. People wanted to be minor celebrities and adopted the pathologies of celebrities. PI relies on ignorance and social media / the internet makes ignorance about each others' lives basically impossible while also creating ignorance about other things in unpredictable ways.

John’s hypothesis is clearly related to Martin Gurri’s analysis of how massive flows of information have eroded elite authority—nicely explained and elaborated on in this recent review by

on . John takes it a step further. It’s not just that people now know that elites don’t live up to presumed standards of competence and conduct. It’s that everyone seems to be awful—or at least enough people do that you can feel permitted to be awful yourself. I’m not sure that’s true in general, but it certainly feels true on Twitter.What do you think? Is TMI making people behave badly?

In Defense of My Horrible Way of Speaking

I enjoyed talking about textiles and glamour on this podcast with David Priess, whose area of expertise is international relations. Believe it or not, we had plenty to discuss!

If you listen to the interview, or anything else I’ve recorded, you may hate my voice. Some people even think it represents a character flaw. But it’s just the way I talk. I don’t like it myself, but I’m not willing to invest in speech lessons. There are too many other things I’d like to learn.

And here’s a video that explains in depth.

There is a selection bias on Twitter and other political forums where the worst behavior gets the most prominence, which easily could get one to over-estimate the amount of awful people out there.

If I see or hear bout people behaving in an unseemly manner, I use it as a lesson to try to avoid doing the same.