The Futility of Silicon Valley NIMBYism and an Interview on Dynamism & Illiberalism

Plus a Substack milestone

Not for sale in Atherton

My latest Bloomberg Opinion column looks at some unfortunate, but largely futile, NIMBYism in Silicon Valley’s (and America’s) most expensive town. Here’s the opening":

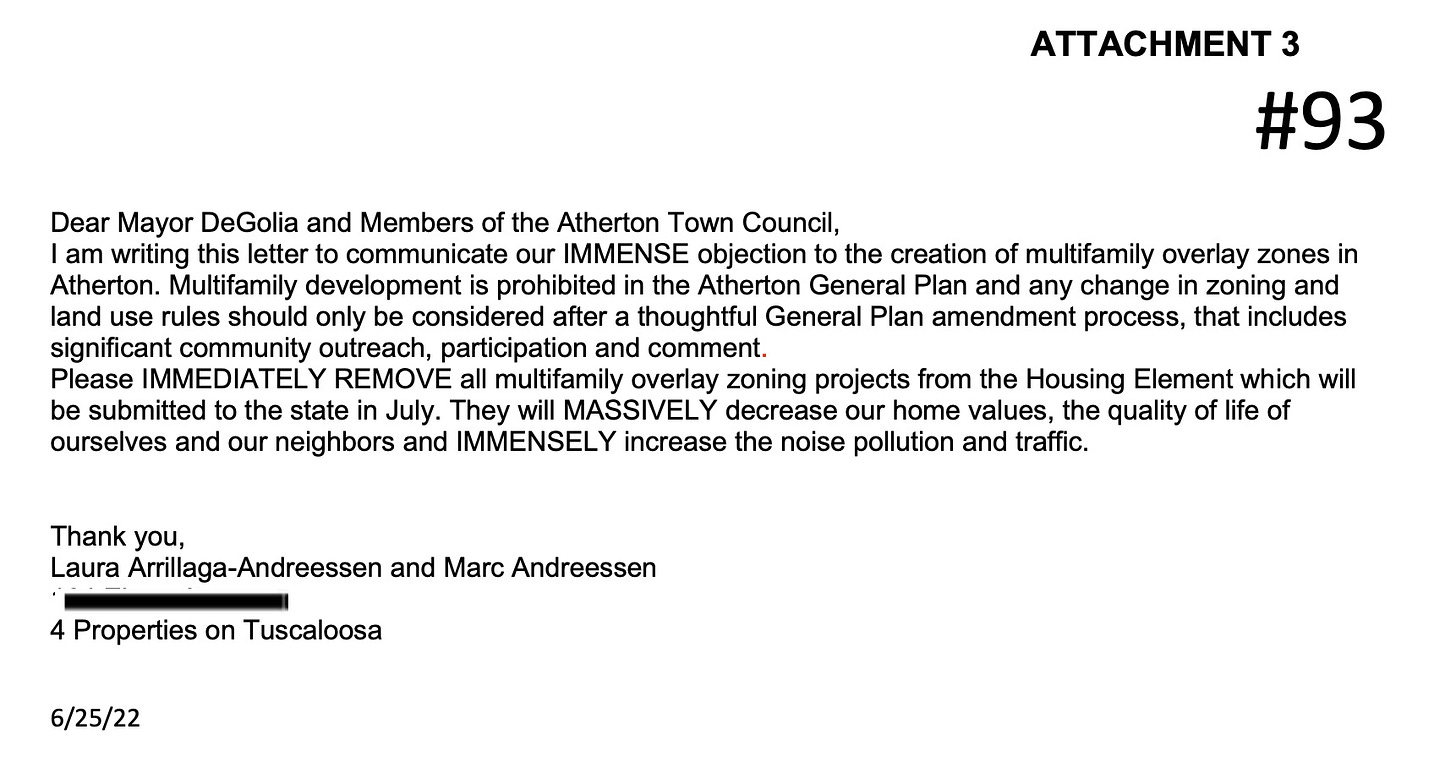

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen got caught last week engaging in housing hypocrisy. The author of a 2020 manifesto called “A Time to Build," Andreessen is a vocal opponent of NIMBYism. Yet when it came to his own town of Atherton, California, Andreessen signed a public comment opposing a plan to add 137 units of multifamily housing by rezoning nine lots. (The comment, written in the first-person singular and a style unlike Andreessen’s, seems to have been composed by his wife.)

An anonymous emailer sent links to the relevant documents and local press coverage to me and, apparently, to Jerusalem Demsas of the Atlantic. Her subsequent article concluded that Andreessen’s hypocrisy illustrates why housing reforms have to take place at the state level, where “officials are influenced by NIMBYs, but they have a much larger electorate to worry about and a mandate to address the cost of living and rising home prices, not just respond and implement local desires.”

The incident proves more than that. It demonstrates that California’s state-level housing reforms are working — not as fast as they ideally would, but working nonetheless

To see what’s going on, read the full thing on Bloomberg Opinion. If you can’t get past the paywall, you can read a version without links at the WaPo, courtesy of my subscription.

Can Liberalism Make Peace Between the Future and Its Enemies?

Aaron Ross Powell, who hosts The Unpopulist’s podcast, interviewed me about my 1998 book The Future and Its Enemies, which he said “looks more and more prescient with every passing day.” Aaron asked excellent, thought-provoking questions and I was having an articulate day. It’s a wide-ranging discussion and I highly recommend listening to the podcast or reading the transcript. Here’s a selection:

Aaron: I was in high school in the 90s. Thinking about gay marriage—you mentioned gay marriage—how dramatic the change on acceptance of gay relationships and gay marriage has been: When I was in high school, Ellen coming out on her sitcom was, like, We're going to have a gay character on television! This was national news; everyone was talking about it. Whereas now, 30 years later, it's just like, so what, there's a gay character.

It happens very quickly, and this makes me think how much of this is about—and going back to the rules, too—ambiguity versus clarity; that people want to know how things are, and how they're going to be. And a lot of rapid change is not constant. It's not uniform. It is experimentation and competing views and figuring out which is the right one, or which is the acceptable one.

All of that messiness means that things are ambiguous, and that what we want is clarity. We want to know, okay, this is the rule that I'm going to have to follow tomorrow. This is what's going to be acceptable. I'm not going to get called out for this. I'm willing to change, but I want to know what it's going to be. That dynamism is inherently ambiguous.

Virginia: Well, I think that is part of it. I think people do want to be able to make their own plans and structure their own lives in a way that it is going to work for them. I would argue that you're better off in a world where people aren't constantly making new rules, from their plans, to run your plans. That's one of the big Dynamist ideas.

But you were talking about people wanting clarity. One of the things that I've written about over the years is clothing sizes and problems of fit. Bear with me; this is relevant. People tend to think that it would be better if there were specific clothing sizes—that if you knew that every size eight dress was for a 35-inch bust and a 28-inch waist (I'm making these up) and 40-inch hips, or something like that, that would be great, because everything would be the same. You would know exactly what you were getting.

It would actually be terrible. In the ‘40s, the catalog companies actually went to the government and said, Could you please establish some standard sizes? And they did. But almost as soon as they were established, different brands started not complying with them, because it wasn't required; it wasn't a regulation.

The reason is that people's bodies come in different proportions—even two people who are the same height and weight. One will have longer legs, one will have shorter arms, one will have a bigger waist, the other will have bigger hips, et cetera. What happens is that brands develop their own fit models and their own sizes. The lack of clarity actually makes it more possible for people to find what fits. I think that is an analogy to one aspect of dynamism—that is, the fact that there isn't a single model that everyone must comply with makes it more likely that people can structure their own lives in meaningful ways.

Now that said, this goes back to this issue of nested rules. Hammering down on people because they express views that were perfectly normal 10 minutes ago, or worse yet, because they use a term in a nonpejorative way (they think), and suddenly, it's turned out that it's now pejorative: This is not good. This is a kind of treating as fundamental rules things that should be flexible and adjustable and tolerant. There is this idea of tolerance when we talk about tolerance as a liberal value, a liberal virtue, but there's also mechanical tolerances. I think a society needs that kind of tolerance as well. That allows for a certain amount of differentiation and pliability; that allows things to work, and it allows people not to be constantly punished. Zero tolerance is a bad idea. Anytime people are having zero tolerance, you're almost always going to be running into trouble.

Read or listen to the whole thing here. Buy The Future and Its Enemies on Amazon here.

A Substack Milestone and a Contest Reminder

I’ve been writing this newsletter for four months and have just crossed the 2,000 subscriber mark. Please spread the word.

In last week’s post, I announced a contest inspired by thoughts from fellow dynamist Substackers Jim Pethokoukis and Anton Howe:

So here’s are the challenges. You can pick one or try any combination.

Write an updated version of the Victorian paragraph, looking back at 2014.

Write a speculative version of the Victorian paragraph, looking back at today from 2030.

Come up with an inspiring illustration of a possible 2040.

I’ll publish a selection of the best here (you’ll retain rights, of course) as I receive them and will accept entries through September 30. I’ll then award the top two in each category a collection of what Jim would call “Up Wing” books. The judging process will depend on how many entries are received, and I reserve the right to award fewer than six prizes. Email them to me at vp@vpostrel.com.

Full background at the original post. I’ve been asked about word limits on the written entries. The inspiration paragraph is about 250 words long. I suspect 250-500 words is the sweet spot, but I don’t want to put limits on readers’ imagination. The only warning is that if you go over 1,000 words you probably won’t get the judges’ full attention unless the writing is riveting.

If you’d like to nominate or donate books as prizes, please email me.

Periodic reminder: If you reply to this email, I will get your message. But unless the note is personal or about the contest, I prefer that you post in the comments below so everyone can see your thoughts.