How I Spent My Summer Vacation

Reading good books and an occasional lousy one. Plus lots of podcasts.

It’s been a long time since my last post and this will be a rambling one. Although I call myself a writer, these days I’m more of a reader.

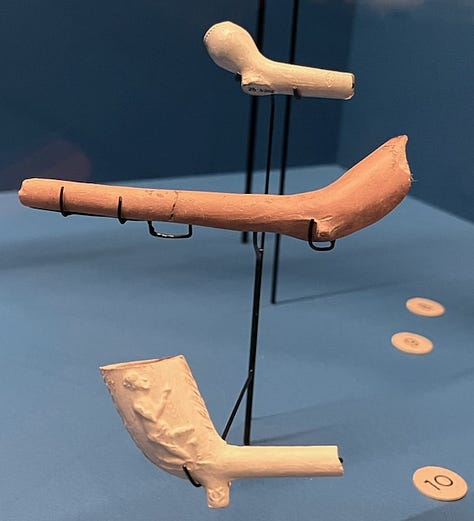

During May, I took a long trip to Pisa, for a weaving workshop, bracketed by stays in London. Particularly in London, I paired reading with experiences. I read Lara Maiklem’s Mud Lark: In Search of London’s Past Along the River Thames (whose U.S. edition has a slightly different title) and visited a related exhibit at the Museum of London. Mudlarking is the hobby of searching the banks of the Thames, a tidal river, at low tide for artifacts from London’s long history. Items on display ranged from an Elizabethan’s child’s shoe (Maiklem’s prize finds) to a tennis champion’s stolen medals. Collected by amateurs, they serve as tangible reminders of everyday lives and the history they made.

I also listened to Helen Castor’s biography of Richard II and Henry IV, The Eagle and the Hart, and attended a performance of Richard II (NYT review here). I love audiobooks but they leave impressions more than the clear memories of traditional readings. I’d like to reread Castor’s history the old-fashioned way. Castor portrays Richard as a man who assumes that, as an annointed king, he has absolute power, with disastrous results. Even in his time, an English king shared power with regional lords and parliament controlled the purse. I couldn’t help thinking about contemporary misconceptions about the is and ought of presidential perogatives.

I also read the manuscript of Brink Lindsey’s The Permanent Problem, which will be published in December. As reading his Substack by the same name suggests, Brink is an exceptionally thoughtful writer and his book deserves the unfortunately overused descriptor thought-provoking. It made me think, especially in the later chapters, and I highly recommend it. My official prepublication blurb:

In this thought-provoking book, Brink Lindsey deepens the intellectual conversation about abundance. Examining the “crisis of dynamism” that stifles growth and the “crisis of inclusion” that limits its beneficiaries, he makes a compelling case that much greater, more widespread abundance is both possible and essential. But human flourishing, he argues, depends crucially on how we navigate the path to that better future. Whatever you think of his proposed cures, Lindsey’s diagnosis demands attention.

At Arnold Kling’s behest, I also read The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West by Alexander Karp, the CEO of Palantir, and Nicholas Zamiska, his aide de camp (officially head of corporate affairs). Arnold reviewed the book and asked me to join him in a conversation about it. Although I agreed with much of it—I think—it is such a colossal mess I can’t entirely be sure. It desperately needed an editor willing to treat the authors like the amateurs they are. This kind of widely praised slipshod work infuriates me. But Arnold and I still had an interesting conversation about dynamism and progress.

It’s been a podcast summer. I spoke with Jarrett Catlin on the California Future Society podcast and Martin Marty of Project Liberal.

Introducing our podcast conversation, the Niskanen Center’s Geoff Kabaservice provides a nice overview of why people interested in progress and abundance are discovering my work.

The intellectual-political discussion of the so-called abundance movement typically is described as a debate taking place almost entirely on the left. But in fact many of its major themes were being discussed in right-leaning circles decades ago. Virginia Postrel, a libertarian thinker and journalist who was the former editor-in-chief of Reason magazine, anticipated much of the current discourse around abundance in her classic 1998 book The Future and Its Enemies: The Growing Conflict Over Creativity, Enterprise, and Progress. Even earlier, in 1990, Postrel was among the first to see that the most important ideological division that was emerging in American politics was not between left and right but between what she called “the proponents of economic dynamism and the advocates of stasis.”

The power of Postrel’s prophecy is evident from even a cursory examination of current politics, in which debates over issues like trade, immigration, housing construction, energy production, and environmental conservation inevitably produce odd-bedfellows coalitions of left and right. Postrel generally approves of center-left advocates of abundance like Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson — since, as she puts it, they share “the convictions that more is better than less, and that a good society is not zero-sum.” But she recently criticized the Klein-Thompson bestseller Abundance for its essentially technocratic mindset, in which change proceeds from central planning without what Postrel regards as sufficient feedback from market mechanisms or public input. She envisions a more libertarian-inflected version of abundance characterized by what she calls “a more emergent, bottom-up approach, imagining an open-ended future that relies less on direction by smart guys with political authority and more on grassroots experimentation, competition, and criticism.”

In this podcast conversation, Postrel analyzes different approaches to what she considers to be the linked causes of abundance and progress — although she notes that progress “tends to code a little right and tends to be more libertarian, more Silicon Valley people” — along with the basic political division between advocates of stasis and dynamism. She talks about her South Carolina origins and her study of the Renaissance, “when dynamism was invented.” She points out that her analysis of dynamism in some measure derived from her love of — and worries about — her adoptive state of California. She discusses some of the thinkers who influenced her analysis, including innovators like Stewart Brand, writers like Jonathan Rauch, Daniel Boorstin, and Henry Petroski, and economists including Friedrich Hayek, Michael Polyani, Mancur Olson, and Paul Romer. And she describes how her interests in dynamism and human invention relate to her interests in textiles, design, fashion, and aesthetics.

Audio and transcript here. I reviewed Abundance here.

On a recent trip to hot, sticky Washington, DC, for an off-the-record discussion of abundance on the right, I was reminded of something I learned about cotton cultivation that didn’t make it into The Fabric of Civilization: Although cotton picking looms large in our historical imaginations, the worst part of cultivating cotton in the U.S., both under slavery and after emancipation, was hoeing cotton—because this process of weeding and thinning took place during the hottest days of summer. Cotton picking happens in the fall. Stay cool.

I enjoy your “rambling.”

I had added Maiklem’s book to my “Books to Read” list when I read a review of it in the Wall Street Journal back in 2019. I was reminded of it when I read about the London Museum exhibit.

I read Helen Castor’s The Eagle and Hart and loved it. I have bought her She-Wolves to read over the summer.

She had a great discussion with Henry Oliver in May

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-common-reader/id1638677512?i=1000708899181

I am looking forward to an upcoming conversation she is having with Tyler Cowen.

Cotton hoeing reminds me that I had a lone black classmate in graduate economics at Harvard, 1952-55, the first who headed a venerable tradition that changed the professional and academic worlds. President Johnson appointed him to the Federal Reserve Board (1966-1974).

Somehow, Andy miraculously got an education, found his way into Doug North's class at University of Washington and Doug got him into Harvard. Not everyone at Harvard was comfortable with Andy there, but we became friends. I was raised by a socialist, anti-racial discrimination, anti-war activist mother so I was proud of Andy.

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/people/andrew-f-brimmer

He had a lovely wife, Doris, and a daughter DR Esther Brimmer who has had a distiguished career in public policy and US Foreign Relations.

https://www.cfr.org/expert/esther-brimmer