From the Archives: Tomato Progress and the Problem of Regulatory Boxes

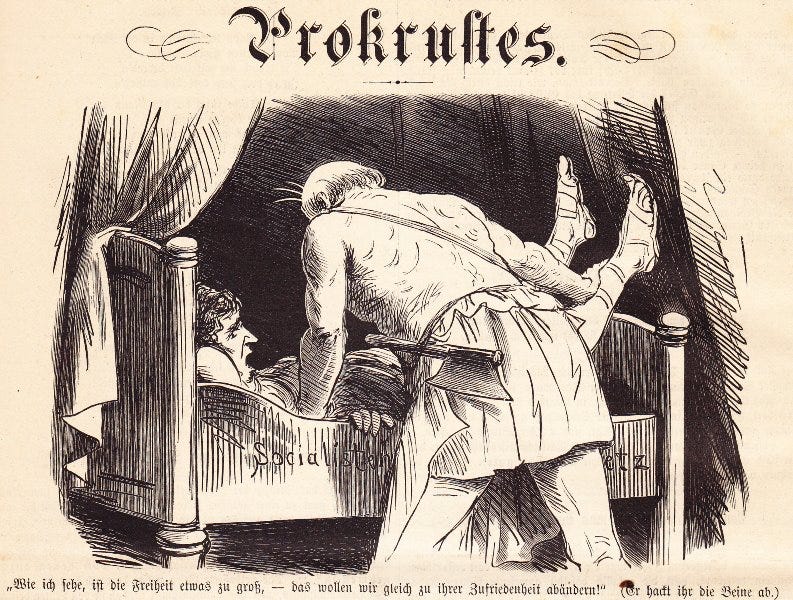

Entrepreneurs need the freedom to test ideas that don’t conform to existing categories.

This article originally appeared as a blog post on April 6, 2004:

If progress is so obvious, why do tomatoes taste so bad? For as long as I can remember, the contrast between delicious tomatoes out of the garden and the rubbery, tasteless variety in supermarkets was Exhibit A in the case against large-scale agriculture. In the early '90s, a biotech company tried to genetically engineer a good tomato. They attracted a lot of hostility from the likes of Jeremy Rifkin but ultimately failed in their quest.

Over the last couple of years, however, delicious tomatoes have hit the supermarkets--in miniature form. Where did these grape tomatoes come from? And could anything that tastes so good actually be low in calories? As I was wolfing some down like candy last night, I wondered about these questions and, using Google, found the story behind them, a long feature by Carole Sugarman of the WaPost. I suspect no one read it at the time (it's dated 9/12/2001) but it's well worth a read now. The story has all the elements of a contemporary business yarn--globalization, intellectual property disputes, secretive business deals--but no new-fangled biotech. It's all old-fashioned grafting, upsetting to Marvell's mower but no bit deal to today's bio-Luddites. Here are some excerpts:

In a few weeks, when most of the locally grown tomatoes disappear, there will still be hope for the brisk-weather salad. A juicy beefsteak may be hard to come by, a pint of farmers' market cherry tomatoes may be scarce, but commercially grown grape tomatoes -- the bite-size sugary fruit that has gone from novelty to commodity -- will be in abundance.

"Meteoric," is how Tom Mueller, director of sales and marketing for Six L's Packing Co., Inc., an Immokalee, Fla., grower, describes their rise in popularity.

After years of producing flavorless, armor-thick impostors, commercial tomato growers now have a big hit. Grape tomatoes are sold widely, from Wal-Mart to Sutton Place Gourmet. Aside from Florida, they're being grown in Mexico and up and down the East and West coasts, making them available all year long. Six L's, for example, farms grape tomatoes in Virginia in the summer, working its way down the coast to Florida by the end of October.

And their ubiquitousness has changed the landscape of the supermarket produce aisle.

Grapes "have killed the cherry tomato business," says Charles Lester, produce buyer for Giant Food, who added that the chain "very seldom" carries cherry tomatoes anymore. They're "quickly becoming the tomato of choice," says Craig Muckle, spokesman for Safeway, which sells 10 times more grape than cherry tomatoes....

Their success, however, is more than just a triumph of taste. The forces of the global marketplace have growers constantly scrambling to come up with the next great idea. New varieties of produce are being imported "from Holland, Costa Rica, all over the world," says Gene McAvoy, an extension agent with the University of Florida. "If growers don't stay ahead of the pack, they're in trouble. People don't just want a pepper anymore."

They also don't just want a tomato, which is why grape tomatoes hit such a competitive nerve among growers. It also explains how the efforts of a small Florida farmer developed into a legal battle, a seed crisis and eventually an oversupply of the tomatoes.

Andrew Chu, a vegetable grower in Wimauma, Fla., first heard about a grape-shaped variety of cherry tomato in 1996. A Taiwanese friend and specialty produce wholesaler in New York asked Chu to try them, thinking they might appeal to Asian shoppers; they were already being grown in mainland China.

So Chu sent away for the hybrid seeds from Known-You Seed Co., Ltd., in Taiwan. He planted his first crop in the fall of 1996. Asians bought the grape-shaped tomatoes, but the market was limited, says Chu.

"I started thinking about taking them mainstream," he says. So in 1997, Chu Farms packed them up in pint-size plastic clamshells, and shipped them through its regular distributors to the East Coast.

Word travels fast among the farmers, seed salespeople and truck drivers in tomato country. Before long commercial growers such as Six L's and Procacci Bros. got a taste of the fruit and realized Chu was on to something. "I've been in business 53 years and I recognized their potential," says Joe Procacci, chief executive officer of Procacci Bros., who first saw the sweet tomatoes at Chu's initial three-acre plot. He and other growers imported the seeds -- a variety called Santa -- and started planting.

As far as I can tell from online sources, grape tomatoes do in fact have few calories, about 33 in a half cup.

Update: Grape tomato innovation continues. In recent years, Cornell professor Phillip Griffiths has created the “Galaxy Suite” of six new varieties in multiple colors. They include “the yellow fingerling Starlight, orange grape-shaped Sungrazer, small red grape-shaped Comet, marbled and striped Supernova, and dark purple pear-shaped Midnight Pear,” all introduced in 2019, and the “Moonshadow, a deeply pigmented purplish-red, oblong tomato” introduced in 2021.

In response to my blog post, Tim Worstall went looking for grape tomatoes in Portugal, where he was living at the time. He found that they were illegal in the EU—not because anyone had explicitly forbidden them but because they didn’t fit into existing categories. Tim was not happy. From his subsequent writeup:

In the 4 years since the EU last passed a regulation about tomatoes, a completely new type has arisen which virtually wipes out the type they last amended the regulation for. Wouldn't it be simpler simply not to have the regulation ? Or we could continue to change the regulations I suppose, as new technologies, types, breeds come along. Sure. First, hire your Brussels lobbyist, then fight through the bureaucracy, get the item onto the agenda, hope that no one objects at the Farm Minister's meeting ( and you can bet that if France has a large cherry tomato growing industry they will ) and then a new regulation is passed : some years and millions of euros later, for a tomato for the Lord's sake!

I don’t know if grape tomatoes are still verboten in the EU, but the mismatch between regulatory categories and new ideas continues to plague us. Here’s another “from the archives” piece, originally published on Bloomberg Opinion on December 12, 2016.

The New York officials and hotel interests who want to drive Airbnb Inc. out of the city call the rentals “unregulated hotels” or “illegal hotels.” These accommodations do, of course, compete with hotels. That’s why Mike Barnello, the chief executive of LaSalle Hotel Properties, told analysts that New York’s draconian new law, which imposes fines of up to $7,500 on absent Airbnb hosts, “should be a big boost in the arm” for his business, “certainly in terms of the pricing.”

But no one who has stayed in an Airbnb -- and I have stayed in many -- would confuse them with hotels.

When your hotel toilet clogs, you simply call the desk. When your flight is delayed and you arrive at 2 a.m., you know someone will be there to check you in. You will never be stuck at midnight unable to get into your hotel because the lock box is frozen shut. Nor will you discover every inch of closet and drawer space occupied by the owner’s clothes. Staying in an Airbnb requires resilience, and sometimes an emergency hotel room.1

Despite the occasional difficulties, Airbnb offers a different kind of value for travelers. It’s like the meal kits sold by companies such as Blue Apron Inc.: It gives you the ingredients for a local living experience, but you still have to do some work. Hotels, by contrast, are like restaurants. They prepare everything for you. New York Airbnbs may be illegal, but they are definitely not hotels.

Airbnb and Blue Apron are but two examples of the “permissionless innovation” that is so important to economic growth. Entrepreneurs need the freedom to test ideas that don’t conform to existing categories. New value often comes from trade-offs and combinations that regulatory definitions never envisioned and might not approve. A better name for these businesses might be “category-free” or “uncorseted” innovation.

Take restaurants like Panera Bread Co. Offering no waiter service but higher-quality ingredients than casual chains, they’re neither sit-down restaurants nor fast food. Hence the need for the new term “fast casual.” Over the past decade, satisfied customers have made fast-casual restaurants the fastest-growing industry segment. But this new definition of quality can, believe it or not, produce regulatory problems.

To some neighborhood activists near the University of California at Los Angeles, the only good restaurant is one with sit-down service and china plates. Anything else is fast food, appealing to (ugh) students and hospital workers, and must be strictly limited by law. So the now-defunct Chili’s and Acapulco restaurants were OK. But after city planners approved Panera, an activist appeal blocked it from opening for two more years.2

This rigidity isn’t an isolated example. Not so long ago, Starbucks Corp. created a radical new concept in American retailing: a neighborhood watering hole where, in the words of founder Howard Schultz, “no one is carded and no one is drunk.” When the company wanted to open stores in San Francisco, it discovered that many neighborhoods had banned the conversion of retail spaces into restaurants, reflecting a surprisingly common city-planning prejudice against eating out. Starbucks could sell coffee to go, but it couldn’t give customers anywhere to sit unless it located in busy shopping districts away from where people lived. Already a well-established company, Starbucks lobbied to get a new zoning category created, “beverage houses.” Now you can find all sorts of coffeehouses in San Francisco neighborhoods where they were once forbidden. But that only happened because a wealthy company had the resources to survive in less desirable locations while it worked to change the rules.

Rigid categories hamper all sorts of unanticipated business ideas. Every new financial product must get shunted into an existing regulatory classification, regardless of its uniqueness. African-style hair braiders find themselves subject to licensing standards designed for hairdressers who use chemicals. Eyebrow threaders run into similar problems.

Or consider medicine. Facing the terrifying prospect of bacteria that resist even the strongest antibiotic drugs, the world desperately needs new ways to fight infections. One potential alternative is phage therapy, which uses tailored and dynamic cocktails of bacteria-attacking viruses. But this approach doesn’t fit into how the U.S. regulates new drugs. Microbiologist Eric C. Keen writes that

The FDA has essentially grafted its traditional antibiotic regulatory protocols onto phage therapy, meaning that all components of a phage cocktail must go through individual clinical trials and that the composition of these cocktails cannot be altered without re-approval. This policy does not reflect the fundamental differences between phages and antibiotics, and would, if perpetuated, likely render phage therapy both prohibitively expensive and significantly less effective.

Although phage therapy does face other economic and technical obstacles, labeling it a “drug” hinders innovators who might make it viable. Instead of demanding new trials for each new combination, Keen proposes a workaround: regulating the process by which the cocktails are produced, the way the Food and Drug Administration checks each year’s FluMist vaccine.

Finding such clever ways to assign new ideas to existing regulatory categories is all-too-often crucial to survival. Uber Technologies Inc. initially avoided hostile local taxi commissions by getting itself regulated by the California Public Utility Commission as a “pre-arranged” black car service. Its app simply made the pre-arrangement nearly instantaneous. Lyft Inc. (and now-defunct Sidecar), meanwhile, pioneered the ride-sharing model with nonprofessional drivers by declaring passengers’ payments “donations.” This transparent ruse gave the concept enough time to build public support and get the utility commission to give ride-hailing services their own regulatory category.

The toughest challenge in economic life is discovering what consumers want that doesn’t already exist and making it happen. The world of potential goods and services has an infinite number of incremental trade-offs and combinations of features, any one of which might be the next big thing. Regulatory power, by contrast, requires a finite number of rigid categories into which every new idea must be crammed, no matter how it is deformed in the process. The more regulations extend throughout the economy, the tighter the corset hampering innovation.

All real examples from my stays at Airbnbs.

When I reported this (Bawdlerized but informative) story on Westwood Village, I learned that the UCLA student organization has done an end run around the regulations. They’ve invited popular fast-casual restaurants, such as Blaze Pizza and Panda Express, to open on campus, which is state property where the rules don’t apply. Good for students, not so good for off-campus folks who might want to frequent them.

This article caused me considerable trouble. It induced me to snack impulsively on the grape tomatoes sitting on our counter. So, when my wife went to make a salad, there were only three left. Raised eyebrows ensued. :)