From the Archives: Christmas Stockings Are an Industrial Triumph

And a new essay on meat grown from cells.

The Colkets’ stockings, including the vintage golf stocking marked by the yellow arrow and show separately in the second photo. Click the photo to see a larger version where you can see the red mending thread.

This article originally ran in The Wall Street Journal this time last year.

Most of the stockings hanging from the Colket family’s suburban Philadelphia mantle this Christmas are what you would expect in 21st-century America. They are decorated with seasonal images in festive red, green and white. To make room for presents, they have unusually wide calves and broad, stubby feet. Rare is the person they’d fit and, given their thick seams, rarer still the shoes. Christmas stockings are symbolic gift containers, not hosiery.

But one of the Colkets’ stockings is different. It’s long and skinny, with a diamond checkered pattern knitted in cream and brown and darned with scattered bits of bright red yarn. “It was a men’s stocking my grandfather wore when golfing and wearing his plus fours,” explains Andrew Colket, who got the stocking from his father as a child and last year passed it down for his son’s first Christmas.

Using an actual sock isn’t a Colket family quirk. All Christmas stockings used to be real hosiery. They weren’t made from velvet or felt or embroidered with the owner’s name. They featured no appliqués, needlepoint or glitter; no reindeer, snowflakes or trees. They were the same knitted socks their owners wore every day. Stockings made ideal gift receptacles because everybody had them, and the knitted cloth could stretch to hold oddly shaped items. Special socks just for receiving Christmas gifts would have been a wildly impractical extravagance.

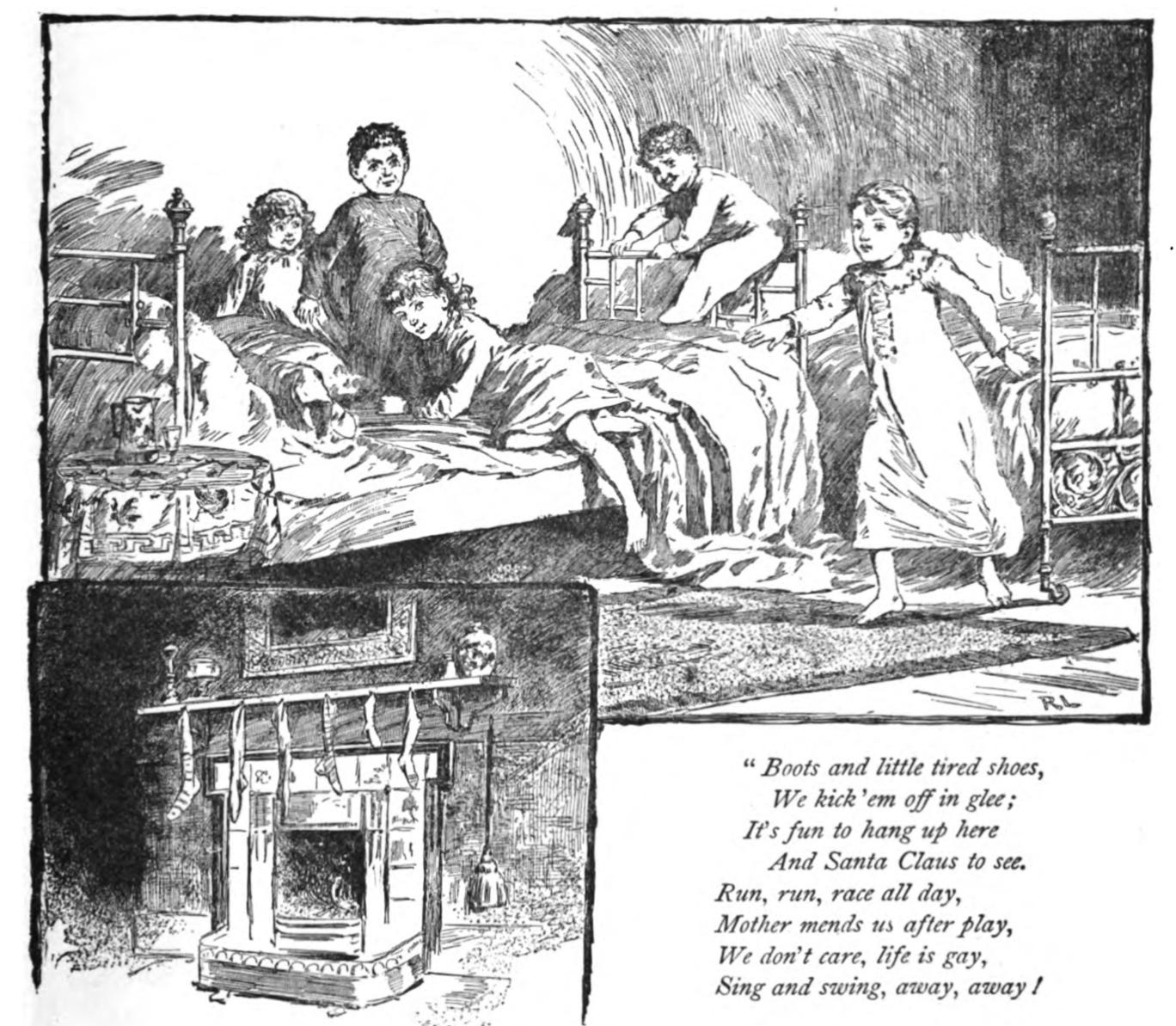

In “Song of the Christmas Stockings,” a children’s poem from the 1880s, a boy wakes up in the middle of the night before Christmas and discovers the stockings swinging from their hooks and celebrating their holiday hiatus:

All day we carry toes,

To-night we carry candy;

Christmas comes once a year

Very nice and handy….

Boots and little tired shoes,

We kick ’em off in glee;

It’s fun to hang up here

And Santa Claus to see.

In most countries, children put out shoes for the local version of Santa, not socks. Christmas stockings are an Anglo-American tradition, which is no accident: It was England that made stockings one of the earliest mass consumer goods. Originally an Italian luxury made of silk, knitted stockings first became everyday apparel in the 16th century, when the English started knitting them from wool. By the end of the 17th century, English manufacturers were exporting 1.75 million pairs a year and supplying another 10 million pairs to the domestic market. Most were made by hand knitters through a “putting-out” system. Manufacturers supplied knitters with working capital in the form of yarn and paid them by the pair.

Others were sewn from knitted fabric made on a machine called a stocking frame, which could knit a row in a single pass. Invented in 1589, the stocking frame steadily improved over time. Although foot powered, it was a complex apparatus: Each stocking frame required more than 2,000 components, including fine needles that challenged the blacksmith’s art. By the mid-18th century, Britain had around 14,000 stocking frames.

In France, the government restricted stocking frames, known as métiers, to protect hand production. Their wares nonetheless spread to customers of all income levels. “The stocking industry could respond to the new consumer demand only because illegal production and marketing networks were there to service the lower-class consumer,” writes historian Cissie Fairchilds. Examining estate inventories of middle- and lower-class Parisians, she found that 97% owned stockings in 1785, up from 64% in 1725.

Even before the Industrial Revolution, stockings were no longer status symbols aping aristocratic styles but popular apparel, an everyday necessity. Stockings heralded what economic historian Deirdre McCloskey has dubbed the Great Enrichment. They embody the technological innovation, entrepreneurial spirit and cultural attitudes that enabled the centuries-long economic takeoff that lifted global living standards to previously inconceivable levels.

The original stocking frames produced only plain fabric, using the knit stitch. In 1758, Jedediah Strutt of the English city of Derby invented a way to incorporate the contrasting purl stitch and produce ribbed stockings. The flattering new styles boosted the appeal of machine-made hose.

The patented “Derby rib” machine proved highly profitable and indirectly played its own role in the Industrial Revolution: Strutt and his partner financed the first spinning mills built by Richard Arkwright, inventor of the water frame, the fundamental advance that turned spinning from a low-productivity handicraft to a truly industrial product. Before Arkwright’s machines, it would have taken a British spinner about five hours to make enough wool yarn to knit a pair of knee socks. The new machines could do it in minutes; today it takes seconds. Cotton hosiery, more desirable than wool, was one of the first uses of the mills’ newly abundant thread. Spinning machines made stockings and other textiles even more affordable and abundant.

By the end of the 19th century, industrial textile production had made cloth cheap enough, and a broad middle class rich enough, that people could consider buying purpose-made “stockings” just to hold Christmas presents. An 1892 Ladies' Home Journal column introduced readers to the “pretty French custom” of giving one’s gentleman friend a “fanciful stocking” made of flannel and bedecked with bells. The giver would fill it with inexpensive gifts, each wrapped in tissue paper accompanied by a jokey note (“My bark is worse than my bite” for a chocolate dog). For a more serious relationship, the stocking could conceal a more expensive gift: “If it is your betrothed, and you are sending him a pair of sleeve links, a scarf pin or any small present,” advised the columnist, “put it down in the extreme toe, so that after he has laughed over all the folly the veritable Christmas gift is reached at last.”

Today, the Colkets’ heirloom stocking has a nostalgic charm; it is an antique eccentricity in a world of purpose-made Christmas stockings. For most of history, however, there was nothing charming about the scarcity of cloth and the dearness of hosiery. It was industrial ingenuity and entrepreneurial zest that made the special Christmas stocking a container for the excitement of an expectant child.

Tastes like chicken…

In my latest essay, published in The Wall Street Journal’ Weekend Review section, I look at the potential ramifications of meat produced with synthetic biology. (Stay tuned for a much longer essay on synbio, coming after the first of the year.) Excerpt:

Synbio executives talk like animal lovers and environmental activists. But synbio is still a form of engineering, a science of the artificial. As such, its ethical appeal represents a significant cultural shift. Since the first Earth Day in 1970, businesses large and small have emerged from the conviction that “natural” foods, fibers, cosmetics, and other products are better for people and the planet. It’s an attitude that harks back to the 18th- and 19th-century Romantics: The natural is safe and pure, authentic and virtuous. The artificial is tainted and deceptive, a dangerous fake. Gory details aside, the “factory” in factory farming makes it sound inherently bad.

Synthetic biology upends those assumptions, raising environmental and ethical standards by making them easier and more enjoyable to achieve. It could help reverse what the writer Brink Lindsey has dubbed “the anti-Promethean backlash” that began in the late 1960s, defined as “the broad-based cultural turn away from those forms of technological progress that extend and amplify human mastery over the physical world.” Synthetic biologists are manipulating atoms, not merely bits.

The WSJ doesn’t include links, but you can read Brink’s excellent essay on the anti-Promethean backlash here. His Substack

is well worth reading.Read my whole essay here (free link).

Loved the presentation --- economics, technology, religion, etc. -- ending with a satisfying revelation. I am researching the years 1880-1920 for a biography of Eleanor H. Porter, author of Pollyanna. She was a byproduct of the industrial revolution -- a concert musician until the invention of the phonograph (when book publishing was booming ). It was great fun to learn about stockings, too.

Wonderful essay about a minor marvel. I love learning about all these overlooked miracles. A great reminder not to take even small conveniences for granted; they rest upon years, even centuries, of technological knowhow and development.