From the Archives: Casualty of War

How World War I destroyed the “glamour of battle” and made pacifism glamorous.

My 2013 book The Power of Glamour is not about fashion or beauty per se but rather about glamour in many different forms, varying with the audience. “The glamour of battle” is one of the oldest uses of the word as we understand it now—the Scots word “glamour” originally meant a literal magic spell—and military glamour is one of its oldest forms. In this article, which I posted on Medium in June 2014, I look at how the glamour of war ebbed and flowed in the 20th century.

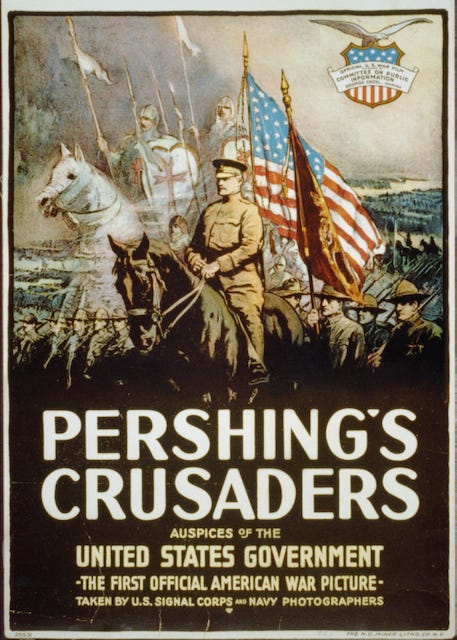

From Achilles, David, and Alexander through knights, samurai, admirals, and airmen, warriors have been icons of masculine glamour, exemplifying courage, prowess, and patriotic significance. Military glamour endures to this day in the iconography of recruiting ads, with their depictions of swift, decisive action, enduring camaraderie, perfect coordination, and meaningful exertion.

In the 19th century, warfare was one of the first contexts in which English speakers used the term glamour in its modern metaphorical sense. (The word originally meant a literal magic spell that made people see things that weren’t there.) “Military heroes who give up their lives in the flush and excitement and glamour of battle,” opined a U.S. congressman in 1885, “are sustained in the discharge of duty by the rush and conflict of physical forces, the hope of earthly glory and renown.”

Even people who hated military life could feel the attraction. Writing after the briefest of conscriptions (a single night in the barracks), D.H. Lawrence in 1916 lamented “this terrible glamour of camaraderie, which is the glamour of Homer and of all militarism.”

The slaughter and apparent futility of the Great War changed all that. Peace activists and bitter veterans now saw the “glamour of battle” as a dangerous delusion rather than a valuable inspiration. “Are you going to tell your children the truth about what you endured,” an American challenged fellow veterans in 1921, “or gild your reminiscences with glamour that will make them want to have a merry war experience of their own?” In 1919, the British painter Paul Nash wrote that the purpose of The Menin Road, his bleak portrait of a desolate and blasted landscape, was “to rob war of the last shred of glory[,] the last shine of glamour.”

The postwar disillusionment did more than create a more realistic perception of warfare. It engendered a successful campaign to make pacifism fashionable. “I do not believe that politicians and financiers could drive men into war unless they first succeeded in hypnotising them with the glamour of noble ideals. It is ‘up to’ the Pacifist to throw the same glamour round his ideals of peace,” wrote an activist in 1917. By 1933, the British journalist Nerina Shute recalled in her memoirs, “the glamour of pacifism had twined itself round the ideals of the writers and preachers and thinkers whose names were best known to the public. Pacifism filled the newspapers.”

The trend extended to the world capital of glamour, Hollywood. In her path-breaking 1939 book America at the Movies, Margaret Farrand Thorp recounted a fan magazine’s report on one example of the era’s glamorous pacifism:

Deanna Durbin is a pacifist. She showed a reporter her school history book with a paragraph which she had underlined with red pencil. “It was Nicholas Murray Butler’s estimate that for the money spent on the World War every family in ten countries could have had a $2,500 house, $1,000 worth of furniture, several acres of land [and so on]. ‘Isn’t it dreadful?’ said Deanna. ‘Not so much the money, as the millions of people killed.’” Ten years ago such a statement would not have added to the glamour of a youthful star, but at least it is safely away from present conflicts.

Thorp’s deadpan final comment suggests what the new glamour of pacifism had in common with the old glamour of battle. Like all forms of glamour, they both contained an element of illusion: a deceptive grace concealing disquieting realities, whether the horrors of the trenches or the threat of Hitler unopposed.

Within a few years, Durbin was a favorite of British troops and reportedly of Winston Churchill as well. Just as World War I punctured the glamour of battle, the Nazi advance largely did away with the glamour of pacifism.

This is not correct. The post WW I anti-war movement was simply an affirmation of pre-war opposition. War had lost its glamour BEFORE WW I, and in the uS there was widespread opposition to entering. Woodrow Wilson won election for his neutral stance. Eugene V. Debs opposed the war, was jailed, ran for President from his jail cell polling nearly a million votes; not because he was a socialist but because he championed the movement against the war and was a hero. There was opposition to WW I conscription with large numbers of military age men refusing to register. Opposition easily compares with that against the Vietnam War.....VERNON SMITH

I grew up amongst pacifist/socialists. My mother cast her first vote for Debs in 1920, and my first was for Norman Thomas in 1948. He was a founder of the Fellowship for Reconciliation. But we, or at least I, switched to support WW II after Pearl Harbor. I was at Eleven worth, KS getting my physical in August, 1945 when the first bomb was dropped. After the second I registered as a pacifist. J.R. Oppenheimer lectured in my freshman physics class at Caltech, we loved him as a great physicist but especially for his personal integrity. I had Linus Pauling for freshman chemistry, the only winner of two undivided Noble prizes--chemistry and peace. Citizen dissent on war was and is central to the American Experiment.