Lately I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about the world that my two daughters — both under the age of three— will inhabit when they’re adults. Last night, I was surprised to find that my older daughter Yara was able to recognize a 1980s-style tape deck in a picture book we were reading (“this… a… music box,” she said, after studying it intently). And she certainly knows what the mail is — in fact, one of her favorite books is called The Jolly Postman.

But will the adult Yara personally write out and mail letters? Perhaps about as frequently as she will play cassette tapes. Which is to say: not never, but almost never.

What I am writing right now is, of course, a letter of a sort. (One that, incidentally, I’ve just turned on optional paid subscriptions for — though all regular posts are and will remain free, as they have since Res Obscura began as a blog over 14 years ago).

The ‘letter’ part of ‘digital newsletter’ is more than just a linguistic fossil. It’s a reminder of how communication technologies evolve not by replacement but by layering, with older forms becoming decontextualized rather than disappearing entirely. Newsletters were once handwritten notes distributed by medieval merchant families to share market-making news. Already by the 17th century, the advent of print had removed this personalized element. Now the entire concept of mail — not just physical mail, but the overall genre of “the letter” as a form of writing, even in electronic form — seems to me to be heading toward extinction, too.

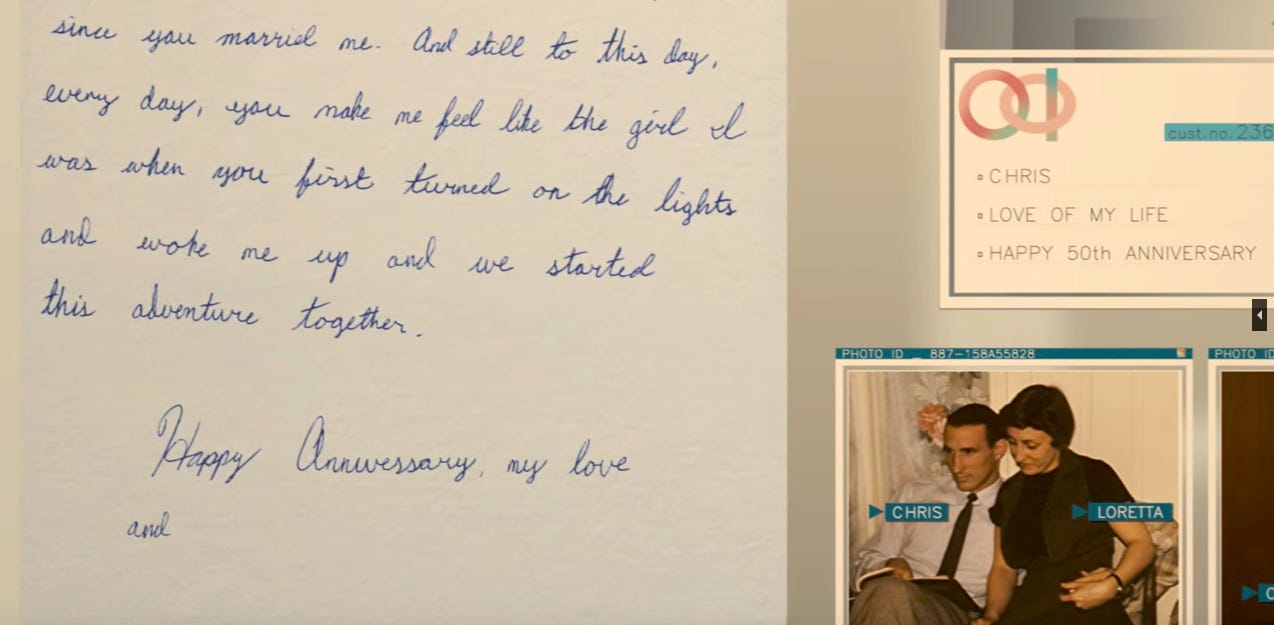

We see this pattern cleverly depicted in earliest scenes of Spike Jonze’s prescient sci-fi film Her (2013). Joaquin Phoenix’s character makes his living writing fake handwritten letters for clients in an age of AI-generated text. It’s rather like the artisanal Arts and Crafts movement that arose in response to mass production… but which, in the end, became an iconic example of mass production (just try searching “craftsman style” on the Home Depot website). Something which was handmade, personal, and bespoke has retained the appearance of all those things, but lost the reality of them.

Spending my days reading dead people’s mail (which is a big part of what historians do) has given me an unusual perspective on how we communicate. The beginning and end of the postal age were bookends of an ongoing revolution in human communication. To appreciate just how profound this change has been, we need to understand what letter-writing meant to past generations — and what it will mean for us when it’s gone.

Letters were futuristic… and enormously difficult

The era when you could reliably expect to receive 99% or more of information someone was trying to send to you — to have acceptable levels of packet loss, you might say — was really fairly short. This can be a bit confusing to wrap one’s head around, because the practice of writing letters is extremely old. Large swathes of the New Testament consist of letters. As far back as 500 BCE, letters were being sent over thousands of miles via the Angarium communications network of the ancient Persian empire (Herodotus’ description of these Persian messengers later became the unofficial motto of the United States Postal Service — “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds”).

And, of course, the concept of corresponding through written messages sent via couriers goes back much further than that. The infamous “complaint tablets” sent to the unscrupulous Sumerian copper merchant Ea-nāṣir are, effectively, customer complaint letters:

But were these letters that ordinary people — as opposed to Persian emperors or wealthy merchants — could expect to send? More to the point, were they letters that could be reliably expected to reach their destination?

Not really. Postal services prior to the eighteenth century were the domain of a literate elites, which was a very small group throughout human history — no society had literacy rates above ten percent in the premodern era, and most were far lower.

Moreover, even those literate elites spent a great amount of time complaining about communications failures. For instance, during one of my earliest archival research trips as a grad student, I found a cache of letters sent between the 1680s to the 1710s by the Scottish physician and scientist Robert Sibbald. The main takeaway from them was how incredibly frustrating the postal system at the time was. In one letter, Sibbald complained bitterly of a book sent to him which “had miscarried,” complaining that this was “not the first tyme I have been so served.” Later, Sibbald tried to send a packet of “curious books” to a member of the Royal Society in London, but the courier carrying them “had the misfortune to lose them and all his papers in a storme during the Voyage to London… he traveled by land and it seems fell in a river.”

Two things had to change to make letter writing into a form of mass communication.

First, the advent of widespread literacy, which was very much a project of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries — something I wrote about here:

And second, reliable forms of rapid transportation, especially clipper ships and railroads.

We can see this shift in the cache of letters I mentioned above. A reader of Sibbald’s letters in the year 1848 wrote an annotation on one that marveled at the ways that things had progressed from the waterlogged couriers of the 17th century to the futuristic trains of the Steam Age:

On Sat. 19 Feb 1848 a special train brought the budget of ministers to Edinburgh in nine and a half hours, from London.

Tempora mutantur. [‘the times are changed’].

Letters were beautiful, but also took up a huge amount of time

There’s a book I’d love to read called Wm & H’ry about the lively and (at times) strained correspondence between the famous siblings William and Henry James. Here’s a quote from a review of it:

Hallman concludes with a short list, compiled from the letters, illustrating what a “terrible burden” letter writing could be. “For three or 4 weeks in London I did nothing literally nothing, but write letters, day after day,” complains Wm, while H’ry claims to have lost a whole month to a “veritable mountain” of correspondence. Even worse was waiting to receive a letter, which the brothers also complain about. Our email age may offer instant gratification and convenience, but Hallman shows us just how much our written communication lacks not only gravitas but what he refers to as “human frailty and warmth.”

Here’s another letter from William James to the social reformer Pauline Goldmark, who he seems to have been very good friends with. Apparently William and his family adopted a puppy from a friend of Goldmark’s during the summer of 1897 — but now, in December of that year, they were experiencing buyer’s remorse. The pup was “hard to teach, voracious of appetite… just not the sort of dog that we had better keep,” as James put it.

But before he gets to that news, notice the plaintive note he opens with!

He was joking here — sort of. A year and a half later, James was still engaging in humorous self-pity about Goldmark’s failure to reply. Goldmark’s answer, evidently, had not come by post at all, but via the ultra-succinct, ultra-fast, text message-esque medium of the telegraph, a poor replacement indeed for the carefully written multi-page letter: “What a winter of estrangement it has been!... no pups offered and ignored or contemptuously rejected by telegraph,” James wrote to his friend in April of 1899. He even ended the letter with yet another callback to the dog incident: “Now this is a long letter and a good one, and says nothing about pups, so I am disposed to demand an immediate reply. Pray write to me here.”

One takeaway from reading many thousands of letters is that people were genuinely offended when letters failed to merit a reply, in a way that I’m not sure applies to our communication habits today. Likewise with the belabored openings and endings of messages between friends — imagine ending an email or a direct message with the likes of “I remain, most humbly, your faithful friend and servant.”

If you’ve read this far, please consider a paid subscription. Reader support is essential for allowing me to write Res Obscura — one of the few places online with ad-free, original longform historical writing. You’ll receive the same weekly posts as free subscribers, plus:

Occasional special posts

Reader Q&As

Early access to works in progress

To receive new posts and support my work, become a free or paid subscriber now:

Letters were a gateway to where we are

Far beyond email, the social practices and affordances of the letter format helped shape the digital age. For instance, take the example of Alan Turing and Christopher Strachey writing an early computer program that auto-generated love letters, which (according to this interesting post by Alban Leveau-Vallier) they would print and leave around their lab as a practical joke.

These early experiments with automated writing were just one sign of how the culture of letter-writing was evolving. As literacy rates rose and postal systems improved, people began to imagine new ways of connecting through the written word.

The 20th century saw an explosion of practices that prefigured our current digital age: pen pal networks connecting strangers across continents, chain letters that went viral before ‘viral’ was a thing, and messages in bottles that imagined unknown readers somewhere out there in the world.

The above message in a bottle (found by a Redditor in 2018) was written in 1924 by someone I came across in my research for Tripping on Utopia — a British traveler and treasure hunter named Hugh Craggs, who sailed to Galapagos with a young Gregory Bateson.

This sort of thing — the emergence of an amorphous, global network of potential correspondents, reachable at random via chain letters or pen pals — was, in many ways, a dress rehearsal for the internet age.

Today, as my daughter grows up in a world where AI writing assistants are commonplace and letters are rare, I wonder if she'll understand what we gained and lost in this transition. Perhaps the most important legacy of the letter-writing age isn't the letters themselves, but the way they taught us to imagine connecting with unseen others through words alone.

As for myself, I can’t even remember the last time I sent a handwritten letter in the mail. It’s an odd fact of my life that I spend thousands of hours reading physical letters, but precisely none writing them.

In the meantime, though, I’m happy to be sending this message in a bottle to you.

Weekly links

• A 2018 Res Obscura post on how long it took letters to travel in the past.

• A recreation of Turing and Strachey’s love letter generator, yielding text like “HONEY SWEETHEART, YOU ARE MY PASSIONATE HEART, MY PRECIOUS LITTLE LIKING.”

• “He had a flamboyant appearance, typically donning a self-made "uniform" of a green topcoat, scarlet waistcoat, and breeches, with a huge leather sash inset with cast-iron rats... hunting animals Black used included a monkey which he said "didn’t do much", a badger named Polly, and raccoons.” From the Wikipedia page for Jack Black (rat catcher).

• “Dalla Ragione identifies it as a ‘cow-nose’ apple, quite common 600 years ago, extremely rare today and so named because its shape recalls an elongated snout” (Smithsonian on finding defunct fruits in early modern artworks)

If you received this email, it means you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter, written by me, Benjamin Breen. I started Res Obscura (“a hidden thing” in Latin) to communicate my passion for the actual experience of doing history.

If you liked this post, please consider forwarding it to friends. I’d also love to hear from you in the comments.